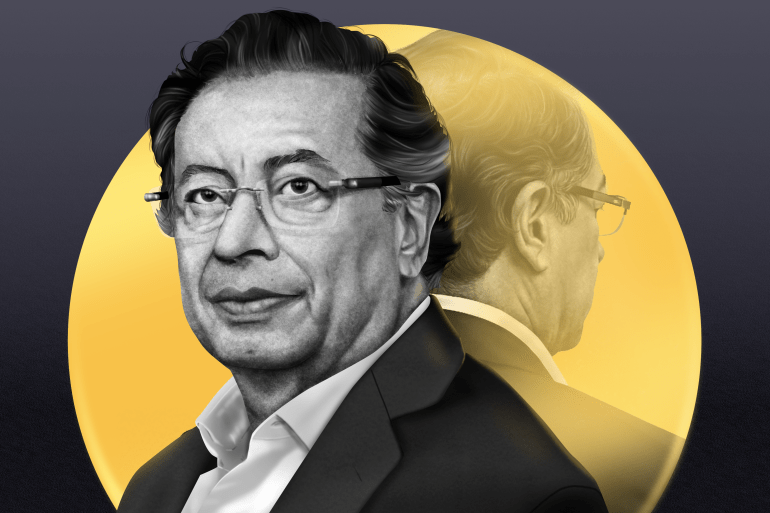

Gustavo Petro: Colombia’s former rebel fighter turned president

From urban rebel to senator facing death threats, what drives Petro, 65, the country’s first progressive president?

Published On 26 Jan 202626 Jan 2026

Save

In 2007, Gustavo Petro was visiting Washington, DC, when he made an unusual request: to accompany his host’s friend on a school pickup run.

At the time, Petro was a rising star in the Colombian Senate who was in the United States to receive the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award for exposing politicians’ ties to paramilitary groups. His host was Sanho Tree, director of drug policy at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS).

“That’s something I can’t do in Colombia,” Tree remembered Petro telling him. “If your assassins know you’re going to pick up your kid at a certain time, that’s extremely dangerous.”

Such dangers were not new to Petro.

He began his career being hunted by soldiers as an armed rebel with the M-19, an underground student movement that sought a fairer, more democratic Colombia. After laying down his rifle, he became a whistleblowing senator, holding hearings on the shadowy alliance between politicians and paramilitary groups that reached the highest echelons of power – and earned him a price on his head from a paramilitary leader.

Throughout, he has pursued the same issues in a country torn apart by decades of armed conflict and where land has long been concentrated in the hands of the wealthy few.

“One thing we can say about Petro is that he’s been consistent,” said Alejandro Gaviria, Petro’s former education minister, who has been both a critic and ally of the president.

“If you watch an interview of his 20 years ago, he has exactly the same ideas. Then he was talking about peace, land reform; he was even ahead of his time talking about environmental issues.”

Advertisement

In 2022, Petro was elected the first left-wing president of the South American country and entered the presidential palace with promises to lead Colombia in a more equitable, eco-friendly direction.

On the international stage, he has been a rare figure among Latin American leaders as an outspoken critic of US President Donald Trump. After the US attacked Venezuela in early January and abducted the country’s leader, Nicolas Maduro, Trump threatened military action against Colombia. The former rebel responded by saying he would “take up arms” again to defend Colombia. A detente soon followed after a phone call between the leaders.

As Petro has struggled to put his ideas into practice throughout his term and faced tensions with Trump, what drives Colombia’s president?

Bookish rebel

Petro was born in 1960 to a middle-class family in the Caribbean coastal town of Cienaga de Oro, but spent much of his childhood in the rainy capital, Bogota, and his teenage years in the city of Zipaquira.

From a young age, he questioned authority.

“He likes discussion, but not dogma,” his father, Gustavo Petro Sierra, once said in an interview where he recalled an incident when his son was three. He had tried to punish his son by slapping his hand, but missed and accidentally struck his face. Petro had looked his father in the eye and yelled, “Don’t hit me in the face, Dad!”

Petro’s father, a teacher, inspired his son’s love of reading, and Petro was particularly influenced by the celebrated novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, by the Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez. His father gave him a copy as a birthday gift when he was a child, according to former Culture Minister Juan David Correa, who met Petro in 2021 as the editor of his memoir.

The magical realism epic immortalises Colombia’s civil wars and class struggles through the saga of the Buendia family through the 19th and early 20th centuries. After independence from Spain in 1810, Colombia experienced intermittent warfare between its two main political factions: the secular, reformist Liberals and the Conservatives, who wanted to maintain the Catholic, colonial status quo.

“That was a book that was definitive in our lives as Colombians,” explained Correa, noting Petro’s belief that Colombians must know their history.

“We have to know who these oligarchies or aristocracies are that ruled the country over the past 200 years of solitude [since independence], as [Petro] called it.”

Advertisement

In the colonial era, the Spanish oversaw a feudal-like system in which landless campesinos (rural workers) toiled for a pittance on behalf of wealthy landowners. In the Colombia that Petro grew up in, this system persisted. Even at the dawn of the new millennium, only 1 percent of landowners possessed half the arable land.

As a boy, Petro’s mother, Clara Nubia Urrego, would tell him stories about the turmoil in the country, including the assassination of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. Gaitan, a presidential candidate for the Liberals, called for reforms, including land distribution, which landowners fiercely opposed. His murder in 1948 kicked off a decade of bloodshed, known as La Violencia, between Liberal armed rebels and the Conservative government.

A truce in 1958 led to a power-sharing arrangement between the Liberal and Conservative parties, known as the National Front. Things had seemingly calmed by the early 1960s, but in 1964, inspired by the Cuban Revolution, the remaining Liberal rebels roaming the countryside came together as the communist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN).

Meanwhile, the National Front blocked any legitimate alternatives, going so far as to rig the election on April 19, 1970 against the populist ANAPO (National Popular Alliance), which attracted people fed up with the two-party system, including Petro’s mother, who had joined the party. Seeing his mother’s sadness at the election results became Petro’s political awakening. He was 10.

At his Catholic school in Zipaquira, Petro and three other friends formed a study group and pledged to dedicate their lives to a better Colombia. They read Alternativa, a left-wing magazine founded by Garcia Marquez, which ran interviews with Chilean and Argentinian rebels and criticised the US sway over Latin America. They became involved with local unions, bringing together workers, salt miners and teachers.

In his memoir, Petro recalls his “communist” beliefs did not make him popular with priests or his classmates whose parents hung portraits of Spain’s fascist dictator General Francisco Franco on their walls. But he credits his high school as the place where he learned about liberation theology, a strand of Catholicism that advocates uplifting the oppressed.

“Since then, love for the poor has remained by my side,” he wrote.

“I didn’t learn that from Marxism, but from liberation theology.”

Occupying a hillside

In 1978, after enrolling at university in Bogota to study economics, Petro was handed a document by Pio Quinto Jaimes, a teacher involved in activist circles. It outlined the goals of an underground student movement known as the 19th of April Movement or M-19, named after the 1970 election. Jaimes was impressed by Petro’s work with the unions and considered him a worthwhile prospect for the group.

Advertisement

Although often described as “urban guerrillas”, M-19 was distinct from the uniformed rebels of the FARC or the ELN. Whereas the FARC recruited from rural workers and wanted a Cuban-style Marxist revolution, M-19 mainly consisted of politicised students who sought social democracy, denied by the two-party system.

Unlike the FARC’s camouflaged commandos, who would raid army outposts before disappearing into the jungle, M-19 operated in the cities and preferred symbolic stunts such as stealing the sword of Simon Bolivar, Colombia’s 19th-century liberation hero, from a Bogota museum.

“Bolivar has not died,” read a note they left behind. “His sword continues his fight. It now falls into our hands, where it is pointed at the hearts of those who exploit Colombia.”

The M-19 hijacked milk trucks to redivert the goods to poorer neighbourhoods, and orchestrated kidnappings targeting Colombia’s wealthy elite.

Petro read the document from cover to cover.

“The movement connected me with the reality of the country, with my mother’s stories about Gaitan, Bolivar, and the ANAPO,” he wrote in his memoirs. “It was as if it had struck a chord that intensely stirred some fibres within me.”

Petro, along with two of his high school study group friends, joined the M-19.

Although he learned to use a gun, he did not take part in armed operations. He was instead tasked with disseminating propaganda. He took on the nom de guerre Aureliano, after a rebel leader in Marquez’s novel.

After graduation, Petro returned to Zipaquira and was elected an ombudsman, a public advocate, in 1981, to hear residents’ complaints about the local government.

In the early 1980s, Petro edited a newsletter – Letter to the People – where he called on readers to occupy a hillside on the outskirts and turn it into a housing project for poor people. Some 400 impoverished families answered the call and found 22-year-old Petro and a group of young activists measuring out 6-by-12 metre (19.7×39.4 feet) plots. There were no wells or sewage, and residents had to collect rainwater.

The squatters were eventually granted permission to stay by the mayor, and the community evolved into a neighbourhood named Bolivar 83.

‘My youth was over’

By 1984, as peace negotiations between the government and M-19 gained momentum, Petro publicly acknowledged his involvement in the group.

“I did so at a demonstration that was one of the largest in the municipality’s history,” he said in an interview. “From then on, my life changed. My youth was over.”

After telling the crowd he belonged to M-19, Petro stepped back to applause.

But not everyone was pleased.

Petro’s father, who had no idea about his son’s secret life, was shocked by the risks he had been taking.

The talks with the government soon fell apart, meaning M-19 members were once again targets for arrest. Petro was forced to go underground.

He lay low in Bolivar 83, sleeping in different beds each night, and wore a disguise, a yellow dress and a wig, pretending to be a woman.

Around this time, Petro had a psychedelic revelation under the guidance of a shaman on a sacred mountain. Drinking ayahuasca, a powerful Amazonian brew, he experienced intense visions. The first showed an Indigenous princess descending from above as he was enveloped by roots.

Advertisement

“What does this mean?” he asked the shaman.

“Well, you are like a spirit taking care of nature,” the spiritual healer replied.

Petro, who recounted this experience in the book Children of the Amazon (2023), said this was the moment he realised his responsibility towards the environment. His second vision was more troubling: he saw his own death during an ambush.

In October 1985, soldiers poured into Bolivar 83, scouring the neighbourhood for M-19 rebels and intimidating residents. A terrified boy revealed the secret tunnels where Petro was hiding.

Petro was arrested, tortured for four days in a military barracks, and imprisoned. He served 16 months for possession of weapons, which he claimed were planted.

While imprisoned, he missed the birth of his first son, Nicolas. Katia Burgos, his wife, who he had known since childhood, was also with M-19.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s internal armed conflict escalated beyond the rebels and the government.

The rise of narcos

The emergence of drug cartels or narcotics traffickers, aka narcos, added another dimension to the conflict.

Cocaine, a white powder refined from coca leaves, gained popularity in the 1970s, fuelled partly by US disco culture. Initially, Colombia was mainly a transit point for cocaine smuggled from Peru or Bolivia, but it was not long before coca cultivation expanded within Colombia, soon becoming the most viable livelihood in rural areas.

Cocaine barons and other wealthy businessmen began bankrolling private armies and paramilitaries to protect their families and property from armed rebels.

Although both were engaged in criminal activities, the rebels sought to overthrow the ruling elite, but the narcos wanted to become part of it, pitting them on opposite sides of the conflict.

After his release from Bogota’s La Modelo prison in 1987 at age 26, the unease of Petro’s rebellion days stuck with him, and he even took to sleeping with an assault rifle under his bed.

The following year, he met Mary Luz Herran, an ardent M-19 member since she was 14. They would go on to marry and have two children, a daughter named Andrea and a son named Andres, before splitting.

Soon after they met, in 1990, the M-19 became the first significant rebel group to demobilise, transforming into the M-19 Democratic Alliance party.

But it was a dangerous time to be in Colombian politics.

In the 1980s and 90s, some 6,000 members of the left-wing Patriotic Union party were killed by narcos, paramilitaries and the security services.

M-19 were not spared, either. In 1990, their presidential candidate, Carlos Pizarro, was shot on board a passenger plane mid-flight.

While serving a term in Congress, Petro began receiving death threats from a paramilitary group called Colsingue, or Colombia Without Guerrillas, and for his and his family’s safety, he agreed to a diplomatic posting in Belgium in 1994. While there, he studied environmentalism and economics at the University of Louvain, and he became deeply interested in the work of Romanian economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who warned that while the global economy relies on constant growth, the Earth cannot be exploited forever.

But Petro grew restless in Brussels. “I felt bored, nostalgic, and eager to return to the political arena,” he writes in his memoirs.

He returned to Colombia, where he was re-elected to Congress in 1998. Two years later, he met his third wife, then a 24-year-old law student named Veronica Alcocer. They soon married, and despite initial tension with Veronica’s father — whom Petro described as an “almost fascist” in an interview with a Colombian magazine — Petro and his father-in-law grew close through their shared love of reading and intellectualism. His funeral in 2012 was one of the few times Petro cried in public. They have two daughters, Sofia and Antonella.

Meanwhile, in a bid to start peace talks in 1998, then-President Andres Pastrana conceded territory roughly the size of Switzerland to Colombia’s largest armed group, the FARC. It was meant to be neutral ground, but the rebels used it to recruit and train child soldiers, grow coca, hold captives and enforce their own brand of justice.

Enter Alvaro Uribe. A right-wing hardliner, Uribe won the 2002 presidential election by promising to quash the rebels with an iron fist.

With US support, Uribe’s beefed-up military inflicted devastating defeats on the FARC. Washington had an interest in stopping the flow of cocaine from the source to the US, and in the 2000s and 2010s, Colombia was the third-largest recipient of US military aid after Israel and Egypt.

Defying death squads

Overall, security improved, but the Uribe era revealed that the authorities had been colluding with paramilitaries for years. While presenting themselves as anti-communist vigilantes, the paramilitaries were responsible for the lion’s share of civilian deaths, terrorising vast swaths of the country.

In one particularly brutal episode in 1997, a band of armed men descended on the village of El Aro in Antioquia. Villagers were brutally tortured and raped, and up to 17 people were killed. The paramilitaries burned the village down as they left, and witnesses reported seeing a helicopter circling above — a yellow aircraft belonging to the Antioquia governor’s office, which at the time was occupied by Uribe.

The ghosts of El Aro were reawakened in the parapolitica (para-politics) scandal of 2006 after journalists and prosecutors revealed that several lawmakers were in league with far-right paramilitary groups, allowing them to murder and intimidate opponents while enriching themselves through bribes and illegal land grabs.

What happened next became one of the defining periods of Petro’s career. He held public hearings and accused the perpetrators of the El Aro massacre of operating with Uribe’s blessing while he was governor, such as by helping establish civilian “self-defence” groups as a front for the militias.

“Why the silence, Mr President?” Petro pressed him at a hearing. “Or does the government accept that violent narcoterrorists have a presence in its ranks?”

The then-president fired back, calling the senator a “terrorist in civilian clothes”. Uribe’s alleged paramilitary ties later landed him in a years-long court case from 2012, ending in his conviction for witness tampering last year, which was soon overturned on appeal.

Having lost comrades like Pizarro to the bloody purges of the 1980s and 90s, Petro knew all too well what he was up against. The scandal established him as a fearless crusader, but won him few friends.

“He was the one to [expose the paramilitaries] at a time when it was incredibly dangerous,” said Gimena Sanchez-Garzoli, a human rights advocate at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA).

“The impunity was so rampant … he was speaking to a Congress where 30 percent of it was linked to these groups.”

Tree, who nominated Petro for the human rights award in DC, remembered how the senator was on edge during this period.

“When I would meet with him in the mid-2000s in Bogota, he couldn’t stand near a window, and every night he had to go home by a different route,” Tree recalled.

Petro’s paranoia about standing near windows was not unwarranted; Salvatore Mancuso, the strongman behind the El Aro massacre, later confirmed that Petro’s name had indeed been on his hit list.

Mayor of Bogota

In 2010, Petro launched his first presidential bid but found himself at odds with his own party, the Democratic Pole, which sidelined him in favour of another candidate. Petro ran anyway and came in third overall.

He founded a new party, Humane Colombia, and successfully ran for mayor of Bogota in 2011.

While the previous mayor and his brother profited from corruption, Petro implemented many progressive reforms. A ban on brandishing firearms in public saw murder rates plunge to a three-decade low. Petro’s administration addressed animal cruelty, stopping the practices of using horse-drawn carts for rubbish collection and bullfighting, and pioneered mobile clinics for homeless drug users, treating addiction as a matter of public health.

“We were the first organisation to propose these [drug] reform ideas,” said Julian Quintero, director of Social Technical Action (ATS), a Bogota-based NGO focused on harm reduction and drug policy reform.

“Petro participated with us, and he sort of embraced the proposals we made to him.”

But Quintero noted that Petro’s governing style was also uneven, characterised by a rapid turnover of staff – a preview of his presidential years.

“Petro did very well as a senator because he’s a very good analyst who trembles with accusations when he’s in the opposition,” Quintero said.

“But when he takes office, he doesn’t stand out for his bureaucratic and technical skills. He’s not a good administrator. He changes teams very quickly, not allowing for continuity in his projects.”

Moreover, he added, in Colombia, “the left isn’t used to governing”.

Quintero noted that deeply entrenched right-wing interests also made Petro’s job more difficult. A failed attempt to overhaul the capital’s waste management system in 2013 ignited a political battle that saw Petro ousted from office by the arch-conservative Attorney General Alejandro Ordonez. That decision drew mass protests, and Petro was reinstated a month later – a sign that his brand of politics was gaining momentum.

Path to victory

In 2010, Petro had lost his presidential bid to Juan Manuel Santos, Uribe’s defence minister, who oversaw his campaign against the FARC in the 2000s. But it was Santos who – to Uribe’s dismay – brokered peace with the rebels in 2016.

When Uribe’s protege Ivan Duque took office in 2018, however, the government largely abandoned that agreement, and violence surged.

“[The Uribe faction] wanted a candidate, basically a puppet, who was to rip up the peace agreement and not let it advance,” WOLA’s Sanchez-Garzoli explained.

Armed groups, including rogue FARC commanders, drug cartels and paramilitaries, rushed to fill the power vacuum, where they once held sway.

Then, in 2021, Duque’s attempt to raise taxes prompted mass protests that were met with police brutality and dozens of deaths. The unrest and growing public disillusionment with the status quo, now fully exposed by the collapsing peace process and the pandemic-ravaged economy, meant Colombia finally had an opening for its first progressive president; a break from the conservative elite such as Uribe and Duque, who came from, and represented the interests of, the wealthy landowning class.

A leftist coalition called the Historic Pact rallied behind Petro for the 2022 elections.

Eager to include Liberals as well, Petro reached out to economist and former government official Gaviria.

“It’s kind of funny because when you see him at a rally, he’s really energised, but in a one-on-one interaction, he is timid, he is quiet, he is difficult to engage in conversation,” Gaviria said, recalling Petro’s visit to his home as he tried to build a coalition.

“When he visited my apartment, I was trying to ask him questions, and he never said anything to me. He stayed silent for five minutes.”

The presidential hopeful eventually proposed that Gaviria, then the Liberals’ presidential candidate, ally with his progressive forces.

Ultimately, in the second round of the election, Gaviria threw his support behind Petro, who offered him a place in his new cabinet as education minister when he took office that August.

International stage

As president, Petro took his message to the world. At his first United Nations speech, he warned, “the jungle is burning” while global powers were fighting over drugs and resources. He highlighted what he saw as the hypocrisy of vilifying cocaine while protecting coal and oil.

“What is more poisonous for humanity, cocaine, coal or oil?” he asked. With Colombia’s cocaine industry having fuelled decades of civil war, Petro has called for cocaine legalisation, calling the so-called war on drugs a failure.

“Cocaine is illegal because it is made in Latin America, not because it is worse than whisky,” he told a broadcast government meeting in February 2025.

In confronting the climate crisis, he has halted fracking and new gas projects to shift Colombia towards clean energy. In an economy reliant on fuel exports, however, this decision has been met with fierce scrutiny.

Petro has also sought to address the country’s armed conflict.

Influenced by French philosopher Jacques Derrida, who believed true forgiveness meant forgiving the unforgivable, Petro presented Congress with a plan to bring all remaining cartels, armed rebels and paramilitaries to the table, including by suspending arrest warrants and empowering local leaders as mediators.

The plan was called “Total Peace”.

‘A dream’

Petro’s peace initiative was put to the test in Buenaventura, a key Colombian port on the Pacific Coast. The port had long been a strategic hub for cocaine smugglers loading cargo onto ships bound worldwide.

Then, in 2019, a deadly turf war exploded. Residents were terrified to leave their homes. In desperation, local archbishop Ruben Dario Jaramillo performed a mass exorcism of the city by spraying the streets with holy water from a convoy of vehicles.

But in October 2022, the leaders of two rival gangs met and shook hands at a church service, thanks to a truce brokered by Jaramillo, building on the Total Peace initiative. The following six weeks saw only one killing, compared with the previous monthly death toll of 25.

The broader peace plan, however, has had flaws. Anticipating a deal, armed groups consolidated their positions to get the upper hand in negotiations while taking advantage of ceasefires to recruit and resupply.

As Quintero observed, the groups calling themselves “guerrillas” today are mostly criminal gangs using the label to legitimise their actions. “There are no guerrillas with the ideology to overthrow the state,” he said.

“[Instead], today there are gangs of very well-armed drug traffickers posing as guerrillas.”

The two most problematic ones are the Gulf Clan and the ELN. The Gulf Clan is a powerful narco-paramilitary crime syndicate demanding talks to negotiate their surrender while aggressively expanding its empire. The ELN continues to carry out attacks and kidnappings and is battling a renegade FARC faction in the dense jungles of Catatumbo, a fertile coca-growing region near Venezuela, displacing tens of thousands of people and prompting Petro to declare a temporary state of emergency last January.

Gaviria said that while reining in heavily armed drug dealers hiding in mountains and jungles would be challenging for any government, Petro has not really had a plan.

“He thought political will was enough to achieve Total Peace, which is completely wrong,” Gaviria said.

He compared Petro’s approach with Santos’s.

“Santos had a strategy, a group negotiating with the FARC. He met with that group every week, having conversations with his experts around the world … he was very disciplined in the way he was conducting this difficult topic.

“Petro was just completely different. No strategy at all,” Gaviria added. “Big announcements and political will. [Petro] thought that was enough, and now we know that no, it was not enough, especially if you’re dealing with such a complex problem.

“Total Peace was not a strategy. Total Peace was an idea, a dream.”

The chaotic nature of Petro’s cabinet has also complicated matters. The turnover rate is high, averaging a new minister every 19 days. Gaviria resigned in early 2023, along with three other ministers, during a fallout over health reforms. And 13 ministers lost or left their jobs in just three months between late 2024 and early 2025.

“I think this is a direct result of his style of policymaking,” said Gaviria, describing it as “undisciplined”.

Petro tends to replace ministers with loyalists and former members of the M-19, while publicly squabbling with former staff and accusing them of disloyalty. Some connect Petro’s perilous past to this governing style.

“Petro has a paranoid style of government that almost defines him,” said Gaviria.

“He is always thinking that there is a conspiracy against him. And probably this idea is related to being a former guerrilla member and living [in hiding].”

Correa agreed, noting that Petro does not trust many people.

The replacements he selects, too, are not necessarily the best-qualified.

For example, Sanchez-Garzoli believes the ELN peace process collapsed because Petro appointed “an ideologue and less of a real negotiator”.

“They basically blew apart a process that could have demobilised thousands,” she explained.

For Gaviria, Petro is these days more interested in ideological battles on social media than in leading the country. “I think he knows that he has not been an effective president,” he said. “Governing a country can be difficult, boring … [and to be successful] you have to engage in difficult conversations. You have to change your mind.”

Petro, he believes, has struggled to accept that “tragic destiny”.

Legacy

Petro’s advocacy on Palestine – and the severing of diplomatic ties with Israel over its genocidal war on Gaza – the climate crisis, drug reform and willingness to confront Trump have won him international praise. Trump, without any evidence, has accused Petro of running cocaine mills and called him a “sick man” on several occasions.

Back home, Petro points to having reduced poverty and infant mortality rates, increased agricultural production, and provided greater access to education, but his criticised peace strategy has failed to deliver broad demobilisation, and stark inequality persists. His approval rating has dropped from 56 percent when he took office to almost 36 percent.

Petro’s presidency has been overshadowed by scandals, including his eldest son Nicolas’s arrest for alleged money laundering linked to narco campaign funding. He calls such attacks targeting his inner circle “lawfare”, aimed at weakening him, something he experienced when he was briefly ousted as mayor of Bogota.

“The first thing they tried to destroy was my family,” he told Spanish daily El Pais last February. “They wanted to destroy the emotional ties because a man without emotional ties becomes hard, bad, and errs.”

He conceded that the presidency is a role that brings him “absolute unhappiness”.

As Petro faces the end of his presidency this year, his legacy may be that of a polarising figure, a revolutionary who tried to overthrow the system from within — yet was unable to solve Colombia’s toughest challenges.

Still, Petro’s supporters see his presidency as the start of a social transformation.

“Our country is a very conservative society; our values, our classism are very, very evident,” said Correa.

“I think that it will take two generations to reconstruct the society … And I think that this government represents only a beginning, a seed for the new generation.”