Why India likely won’t return Hasina to face Bangladesh death penalty

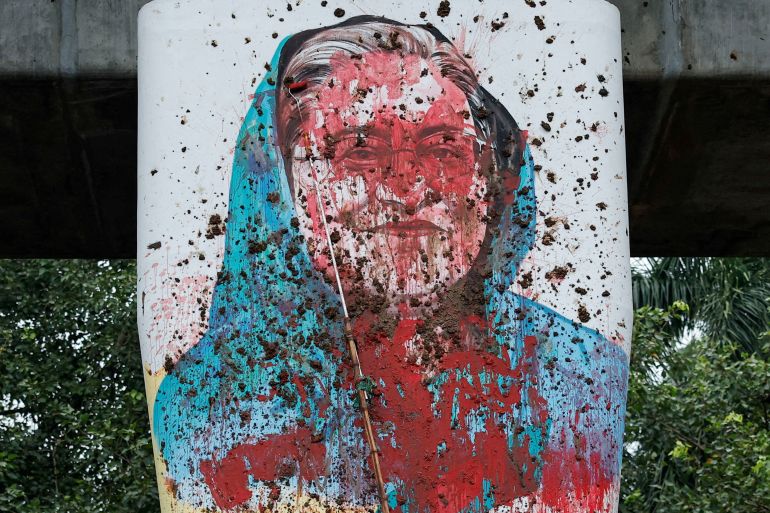

Bangladesh protesters applaud death penalty for former PM Sheikh Hasina, convicted on charges of crimes against humanity. But she is far from the gallows, in India.

Published On 18 Nov 202518 Nov 2025

Published On 18 Nov 202518 Nov 2025

Save

New Delhi, India – Shima Akhter, 24, was in the middle of football practice when her friend stopped the session to break some news for her: Sheikh Hasina, the fugitive former prime minister of Bangladesh, had been sentenced to death.

To the University of Dhaka student, it felt like a moment of vindication.

Several of Akhter’s friends were killed in a crackdown on protesters by Hasina’s security forces last year before Hasina finally quit office and fled Bangladesh. The International Crimes Tribunal in Dhaka, which tried the 78-year-old leader for crimes against humanity, sentenced Hasina to death after a months-long trial that found her guilty of ordering a deadly crackdown on the uprising last year.

“The fascist Hasina thought she could not be defeated, that she could rule forever,” Akhter said from Dhaka. “A death sentence for her is a step towards justice for our martyrs.”

But, Akhter added, the sentencing itself wasn’t enough.

“We want to see her hanged here in Dhaka!” she said.

That won’t happen easily.

Hasina, who fled Dhaka as protesters stormed her home in August 2024, remains far from the gallows for now, living in exile in New Delhi.

Hasina’s presence in India despite repeated requests from Bangladesh to hand her over has been a key source of friction between the South Asian neighbours over the past 15 months. Now, with Hasina formally convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death, those tensions are expected to rise to new heights. Even though India is eager to build a partnership with a post-Hasina Dhaka, several geopolitical analysts said they cannot envision a scenario in which New Delhi turns the former prime minister over to Bangladesh to face the death penalty.

Advertisement

“How can New Delhi push her towards her death?” former Indian High Commissioner to Dhaka Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty said.

‘Highly unfriendly act’

Hasina, Bangladesh’s longest serving prime minister, is the eldest daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who led the war for independence from Pakistan in 1971.

She first became prime minister in 1996. Defeated in the 2001 election, she was out of power until she won again in 2009. She remained in office for 15 years after that, winning elections that opposition parties often boycotted or were banned from contesting in amid a broader hardline turn. Thousands of people were forcibly disappeared. Many were killed extrajudicially. Torture cases became common, and her opponents were jailed without trials.

Meanwhile, her government touted its economic record to justify her rule. Bangladesh, which former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had once called a “basket case” economy, has in recent years witnessed rapid gross domestic product growth and has outpaced India’s per capita income.

But in July 2024, a student protest that initially began over government job quotas for descendants of those who fought in the 1971 war of independence from Pakistan escalated into a nationwide call for Hasina to go after a brutal crackdown by security forces.

Student protesters clashed with armed police in Dhaka, and nearly 1,400 people were killed, according to estimates by the United Nations.

Hasina, a longtime ally of India, fled to New Delhi on August 5, 2024, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus took over as interim leader. Yunus’s government has since moved to build closer ties with Pakistan amid tensions with India, including over Dhaka’s insistence that New Delhi expel Hasina.

On Tuesday, Dhaka’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs raised the pitch against New Delhi further. The ministry cited an extradition agreement with India and said it was an “obligatory responsibility” for New Delhi to ensure Hasina’s return to Bangladesh. It added that it “would be a highly unfriendly act and a disregard for justice” for India to continue to provide Hasina refuge.

Political analysts in India, however, pointed out to Al Jazeera that an exception exists in the extradition treaty in cases in which the offence is “of a political character”.

Advertisement

“India understands this [Hasina’s case] to be political vindictiveness of the ruling political forces in Bangladesh,” said Sanjay Bhardwaj, a professor of South Asian studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

In New Delhi’s view, Bhardwaj told Al Jazeera, Bangladesh is today ruled by “anti-India forces”. Yunus has frequently criticised India, and leaders of the protest movement that ousted Hasina have often blamed New Delhi for its support of the former prime minister.

Against this backdrop, “handing over Hasina would mean legitimising” those opposed to India, Bhardwaj added.

‘India’s equations need change’

India said in a Ministry of External Affairs statement that it has “noted the verdict” against Hasina and New Delhi “will always engage constructively with all stakeholders”.

India said it “remains committed to the best interests of the people of Bangladesh, including in peace, democracy, inclusion and stability in that country”.

Yet the relationship between New Delhi and Dhaka today is frosty. The flourishing economic, security and political alliance that existed under Hasina has now morphed into ties characterised by mistrust.

Chakravarty, the former Indian high commissioner, said he does not expect that to change soon.

“Under this government [in Dhaka], the relationship will remain strained because they will keep saying that India is not giving us Hasina back,” Chakravarty told Al Jazeera.

But he said Bangladesh’s elections scheduled in February could offer a new opening. Even though Hasina’s Awami League is banned from contesting and most other major political forces – including the biggest opposition force, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party – are critics of New Delhi’s, India will find it easier to work with an elected administration.

“We cannot carry on like this, and India needs an elected government in Dhaka,” Chakravarty said of the tense ties between the neighbours. “India should wait and watch but not disturb the other arrangements, like trade, in goodwill.”

Sreeradha Datta, a professor specialising in South Asian studies at India’s Jindal Global University, said India has been caught in a bind over Hasina but is not blind to the popular resentment against her in Bangladesh.

In an ideal scenario, she said, New Delhi would like to see the Awami League back in power in Bangladesh at some point in the future. “She [Hasina] is always the best bet forward for India,” Datta told Al Jazeera.

But the reality, she said, is that India needs to accept that Bangladesh is unlikely to ever give Hasina another chance. Instead, India needs to build ties with other political forces in Dhaka, Datta said.

“India never had a good equation with any of the other stakeholders there. But that has to change now,” Datta said.

“Currently, we are at a very fragile point in the bilateral relations,” she added. “But we have to be able to move past this particular agenda [of Hasina’s extradition].”

Advertisement

Even if India and Bangladesh are no longer allies, they need to “have civility towards each other”, Datta said.

Dividends of clinging to Hasina

Bangladesh and India share close cultural ties and a 4,000km (2,485-mile) border. India is Bangladesh’s second biggest trading partner after China. In fact, trade between India and Bangladesh has increased in recent months despite the tensions.

But even though India has long insisted that its relationship is with Bangladesh and not with any party or leader in Dhaka, it was been closest with the Awami League.

After a bloody war of independence in 1971, Hasina’s father took power in East Pakistan, renamed Bangladesh, with India’s help. For India, the breakup of Pakistan solved a major strategic and security nightmare by turning its eastern neighbour into a friend.

Hasina’s personal relationship with India also goes back nearly as far.

She first called New Delhi her home 50 years ago after most of her family, including Rahman, was assassinated in a military coup in 1975. Only Hasina and her younger sister, Rehana, survived because they were in Germany.

Indira Gandhi, then India’s premier, offered the orphaned daughters of Rahman asylum. Hasina lived at multiple residences in New Delhi with her husband, MA Wazed; children; and Rehana and even moonlighted at All India Radio’s Bangla service.

After six years in exile, Hasina returned to Bangladesh to lead her father’s party and was elected to the prime minister’s office first in 1996 before her second, longer stint started in 2009.

Under her rule, ties with India flourished, even as she faced domestic criticism over brokering deals with Indian firms seen as unfair for Dhaka.

When she was ousted and felt the need to flee, there was little doubt about where she would seek refuge. Ajit Doval, India’s national security adviser, received her when she landed on the outskirts of New Delhi.

“We did not invite Hasina this time,” said Chakravarty, who dealt with Hasina’s government briefly in 2009 when he was high commissioner. “A senior official received her naturally because she was the sitting prime minister, and India allowed her to stay because what other option was there?”

“Can she go back to Bangladesh, more so now when she is on a death sentence?” he asked, adding, “She was a friendly person to India, and India has to take a moral stand.”

Michael Kugelman, a South Asia analyst based in Washington, DC, said Hasina’s presence in India would continue to “remain a thorn in the bilateral relationship” going forward but enabled “India to stay true to its pledge to remain loyal to its allies”.

However, theoretically, there could be longer term political dividends too for New Delhi, Kugelman argued.

Unlike other analysts, Kugelman said Hasina’s political legacy and the future of her Awami League cannot be written off completely.

Hasina leads an old dynastic party, and a look at South Asia’s political history reveals that dynastic parties “fall on hard times and for quite some time, but they don’t really shrivel up and die”, Kugelman said.

“Dynastic parties hang around” in South Asia, he said, and “with patience, if you live longer to see significant political change, it could create new opportunities for comeback.”