Turning point or pointless turn: Will DR Congo-Rwanda deal bring peace?

From critical minerals to M23 and grassroots exclusion, experts weigh in on whether the US-brokered agreement can succeed.

By Gershwin WanneburgPublished On 1 Jul 20251 Jul 2025

Cape Town, South Africa – Five months ago, with a single social media post, United States President Donald Trump put half a million people in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) at risk when he announced the closure of USAID – the single biggest aid donor in the country.

A few days ago in Washington, DC, the same administration claimed credit for extricating the Congolese people from a decades-long conflict often described as the deadliest since World War II. This year alone, thousands of people have died and hundreds of thousands have been displaced.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 items

Will a new deal end war in eastern DR Congo?

end of list

While the White House may be celebrating its diplomatic triumph in brokering a peace deal between tense neighbours DRC and Rwanda, for sceptical observers and people caught up in conflict and deprivation in eastern DRC, the mood is bound to be far more muted, experts say.

“I think a lot of ordinary citizens are hardly moved by the deal and many will wait to see if there are any positives to come out of it,” said Michael Odhiambo, a peace expert for Eirene International in Uvira in eastern DRC, where 250,000 displaced people lost access to water due to Trump’s aid cutbacks.

Odhiambo suggests that for Congolese living in towns controlled by armed groups – like the mineral-rich area of Rubaya, held by M23 rebels – US involvement in the war may cause anxiety, rather than relief.

“There is fear that American peace may be enforced violently as we have seen in Iran. Many citizens simply want peace and even though [this is] dressed up as a peace agreement, there is fear it may lead to future violence that could be justified by America protecting its business interests.”

Advertisement

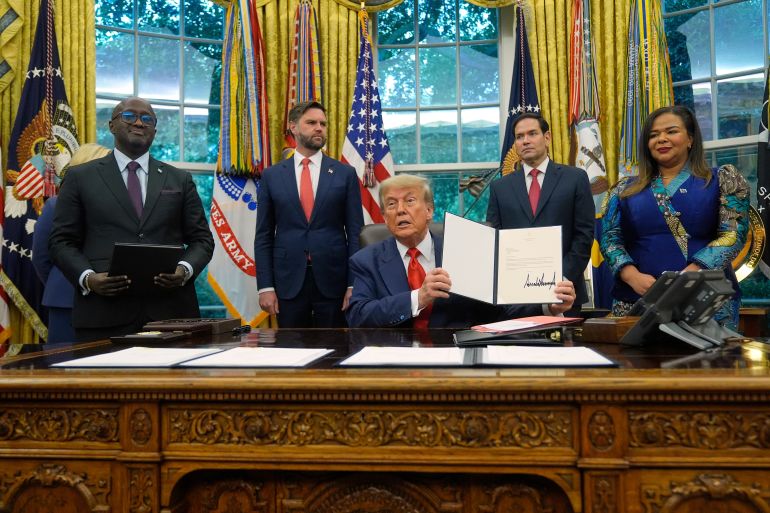

The agreement, signed by the Congolese and Rwandan foreign ministers in Washington on Friday, is an attempt to staunch the bleeding in a conflict that has raged in one form or another since the 1990s.

At the signing, Rwandan Foreign Minister Olivier Nduhungirehe called it a “turning point”, while his Congolese counterpart, Therese Kayikwamba Wagner, said the moment had “been long in coming”.

“It will not erase the pain, but it can begin to restore what conflict has robbed many women, men and children of – safety, dignity and a sense of future,” Wagner said.

Trump has meanwhile said he deserves to be lauded for bringing the parties together, even suggesting that he deserves a Nobel prize for his efforts.

While the deal does aim to quell decades of brutal conflict, observers point to concerns with the fine print: That it was also brokered after Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi said in March that he was willing to partner with the US on a minerals-for-security deal.

Experts say US companies hope to gain access to minerals like tantalum, gold, cobalt, copper and lithium that they desperately need to meet the demand for technology and beat China in the race for Africa’s natural resources.

But this has raised fears among critics that the US’s main interest in the agreement is to further foreign extraction of eastern DRC’s rare earth minerals, which could lead to a replay of the violence seen in past decades, instead of a de-escalation.

M23 and FDLR: Will armed groups fall in line?

The main terms of the peace deal – which is also supported by Qatar – require Kinshasa and Kigali to establish a regional economic integration framework within 90 days and form a joint security coordination mechanism within 30 days. Additionally, the DRC should facilitate the disengagement of the armed group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), after which Rwanda will lift its “defensive measures” inside the DRC.

According to the United Nations and other international rights groups, there are about 3,000 to 4,000 Rwandan troops on the ground in eastern DRC, as Kigali actively backs M23 rebels who have seized key cities in the region this year. Rwanda has repeatedly denied these claims.

M23 is central to the current conflict in eastern DRC. The rebel group, which first took up arms in 2012, was temporarily defeated in 2013 before it reemerged in 2022. This year, it made significant gains, seizing control of the capitals of both North Kivu and South Kivu provinces in January and February.

Advertisement

Although separate Qatar-led mediation efforts are under way regarding the conflict with M23, the rebel group is not part of this agreement signed last week.

“This deal does not concern M23. M23 is a Congolese issue that is going to be discussed in Doha, Qatar. This is a deal between Rwanda and DRC,” Gatete Nyiringabo Ruhumuliza, a Rwandan political commentator, told Al Jazeera’s Inside Story, explaining that the priority for Kigali is the neutralisation of the FDLR – which was established by Hutus linked to the killings of Tutsis in the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

“Rwanda has its own defensive mechanisms [in DRC] that have nothing to do with M23,” Ruhumuliza said, adding that Kigali will remove these mechanisms only once the FDLR is dealt with.

But the omission of M23 from the US-brokered process points to one of the potential cracks in the deal, experts say.

“The impact of the agreement may be more severe on the FDLR as it explicitly requires that it ceases to exist,” said Eirene International’s Odhiambo. “The M23, however, is in a stronger position given the leverage they have from controlling Goma and Bukavu and the income they are generating in the process.”

The US-brokered process requires the countries to support ongoing efforts by Qatar to mediate peace between the DRC and M23. But by including this, the deal also “seems to temper its expectations regarding the M23″, Odhiambo argues.

Additionally, “M23 have the capacity to continue to cause mayhem even if Rwanda decided to act against it,” he said. “Therefore, I think the agreement will not in itself have a major impact on the M23.”

In terms of the current deal’s effect on the two countries, both risk being exposed for their role in the conflict, he added.

“I think that if Rwanda manages to prevail on the M23 as anticipated by the deal, it may prove the long-suspected proxy relationship between them.”

For DRC, he said Kinshasa executing the terms of the agreement will not augur well for the FDLR, but suggested calls to neutralise them may be a tall order.

“If [Kinshasa] manage to do it, then they remove Rwanda’s justification for its activities in the DRC. But to do so may be a big ask given the capacity of the FARDC [DRC military], and failure to do so will feed into the narrative of a dysfunctional and incapable state. Therefore, I think the DRC has more at stake than Rwanda.”

On the other hand, Tshisekedi’s government could score political points, according to Jakob Kerstan, DRC country director for the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Foundation (KAS), which promotes democracy and the rule of law.

“The sentiment … of the Congolese population, it’s very much like the conflict has been left behind: No one really cares in the world; the Congo is only being exploited, and so on. And the fact that there is now a global power caring about the DRC … I think this is a gain,” he said.

He feels there is also less pressure on Kinshasa’s government today than earlier this year when M23 was first making its rapid advance. “There are no protests any more. Of course, people are angry about the situation [in the east], but they kind of accept [it]. And they know that militarily they won’t be able to win it. The Kinshasa government, they know it as well.”

‘Peace for exploitation’?

Although Kinshasa appears to have readily offered the US access to the country’s critical minerals in exchange for security, many observers on the continent find such a deal concerning.

Advertisement

Congolese analyst Kambale Musavuli told Africa Now Radio that reports of the possible allocation of billions of dollars worth of minerals to the US, was the “Berlin Conference 2.0″, referring to the 19th-century meeting during which European powers divided up Africa. Musavuli also bemoaned the lack of accountability for human rights abuses.

Meanwhile, Congolese Nobel laureate Denis Mukwege called the agreement a “scandalous surrender of sovereignty” that validated foreign occupation, exploitation, and decades of impunity.

An unsettling undertone of the deal is “the spectre of resource exploitation, camouflaged as diplomatic triumph”, said political commentator Lindani Zungu, writing in an op-ed for Al Jazeera. “This emerging ‘peace for exploitation’ bargain is one that African nations, particularly the DRC, should never be forced to accept in a postcolonial world order.”

Meanwhile, for others, the US may be the ones who end up with a raw deal.

KAS’s Kerstan believes Trump’s people may have underestimated the complexities of doing business in the DRC – which has scared off many foreign companies in the past.

Even those who welcome this avenue towards peace acknowledge that the situation remains fragile.

Alexandria Maloney, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s US-based Africa Center, praised the Trump deal for combining diplomacy, development and strategic resource management. However, she warned against extraction without investment in infrastructure, skills and environmental safeguards. “Fragile governance structures in eastern DRC, particularly weak institutional capacity and fragmented local authority, could undercut enforcement or public trust,” Maloney told the think tank’s website.

Furthermore, China’s “entrenched footprint in the DRC’s mining sector may complicate implementation and heighten geopolitical tensions”, she added.

For analysts, the most optimistic assessments about the US’s role in this process appear to say: Thank goodness the Americans stepped in; while the least optimistic say: Are they in over their heads?

Overall, this Congo peace agreement seems to have few supporters outside multilateral diplomatic fora such as the UN and the African Union.

For many, the biggest caution is the exclusion of Congolese people and civil society organisations – which is where previous peace efforts have also failed.

“I have no hopes at all [in this deal],” said Vava Tampa, the founder of grassroots Congolese antiwar charity Save the Congo. “There isn’t much difference between this deal and the dozens of other deals that have been made in the past,” he told Al Jazeera’s Inside Story.

“This deal does two things really: It denies Congolese people – Congolese victims and survivors – justice; and simultaneously it also fuels impunity,” he said, calling instead for an international criminal tribunal for Congo and for perpetrators of violence in both Kigali and Kinshasa to be held accountable.

“Peace begins with justice,” Tampa said. “You cannot have peace or stability without justice.”