In Pictures

Preserving Oualata’s fragile manuscript legacy amid desert threats

Centuries-old manuscripts in Oualata libraries face destruction as desert sands encroach on the ancient Mauritanian town.

Published On 28 May 202528 May 2025

Oualata forms part of a quartet of fortified towns, or ksour, granted World Heritage status for their historical significance as trading and religious centres. Today, they preserve vestiges of a rich medieval past.

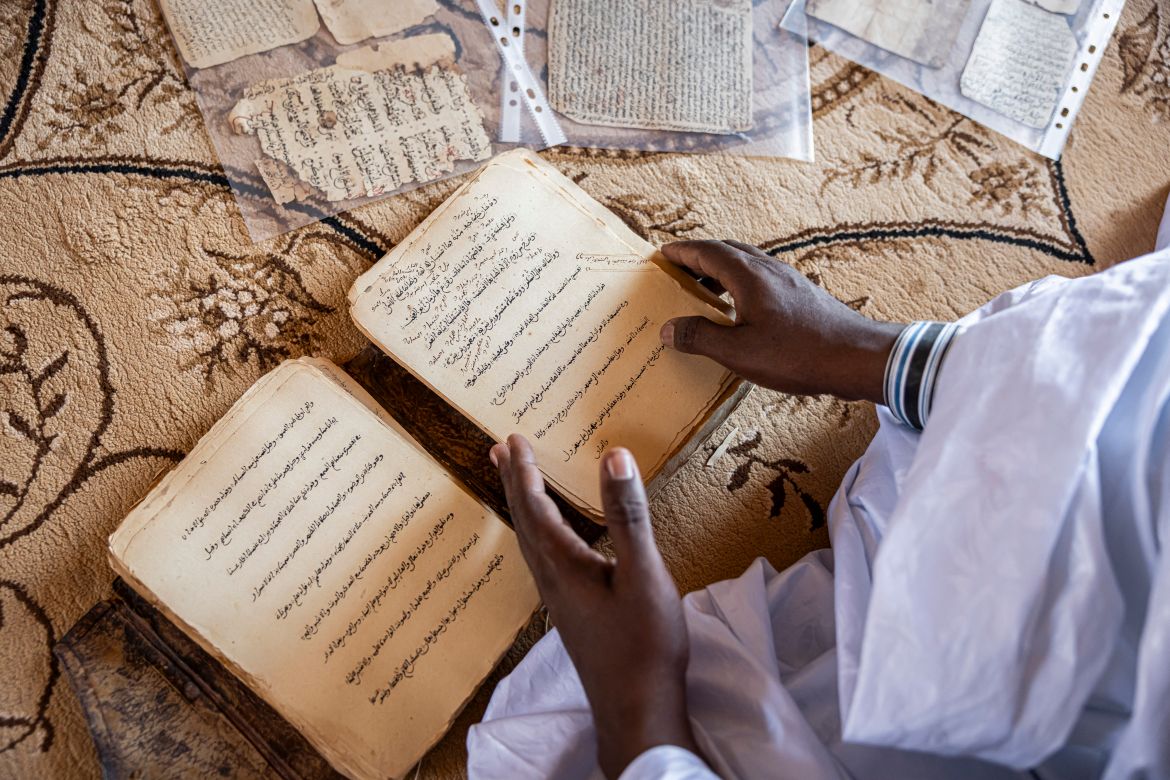

Throughout Oualata, doors fashioned from acacia wood, adorned with traditional designs painted by local women, punctuate the earthen facades. Family libraries safeguard centuries-old manuscripts, invaluable records of cultural and literary heritage passed down through generations.

Yet, Oualata’s proximity to the Malian border leaves it acutely vulnerable to the unforgiving environment of the Sahara. Scorching heat and seasonal downpours have left piles of stone and gaping holes in the town’s historical walls, the aftermath of especially severe recent rains.

“Many houses have collapsed because of the rains,” said Khady, standing beside her crumbling childhood home, now her inheritance from her grandparents.

Depopulation has only accelerated Oualata’s decline.

“The houses became ruins because their owners left them,” explained Sidiya, who is a member of a national foundation dedicated to preserving the country’s ancient towns.

For generations, Oualata’s population has steadily dwindled as residents depart in search of work, leaving the historical buildings neglected. The traditional structures, coated in reddish mud-brick known as banco, were crafted to withstand the desert climate, but require maintenance after each rainy season.

Advertisement

Much of the Old Town now stands abandoned, with only about one-third of its buildings inhabited.

“Our biggest problem is desertification. Oualata is covered in sand everywhere,” Sidiya said.

According to Mauritania’s Ministry of Environment, approximately 80 percent of the country is affected by desertification – an advanced stage of land degradation caused by “climate change (and) inappropriate operating practices”.

By the 1980s, even Oualata’s mosque was submerged in sand. “People were praying on top of the mosque” rather than inside, recalled Bechir Barick, a geography lecturer at Nouakchott University.

Despite the relentless sands and wind, Oualata still preserves relics from its days as a key stop on trans-Saharan caravan routes and a renowned centre of Islamic learning.

As the town’s imam, Mohamed Ben Baty descends from a distinguished line of Quranic scholars and is the custodian of nearly a millennium of scholarship. The family library he oversees houses 223 manuscripts, the oldest dating back to the 14th century.

In a cramped, cluttered room, he half-opened a cupboard to display its precious contents – fragile, centuries-old documents whose survival is nothing short of remarkable.

“These books, at one time, were very poorly maintained and exposed to destruction,” Ben Baty said, gesturing towards pages marked by water stains, now stored in plastic sleeves. “Books in the past were stored in trunks, but when it rains, the water seeps in and can spoil the books,” he explained, recalling when part of the roof collapsed eight years ago during the rainy season.

Advertisement

Spain provided funding in the 1990s for a library in Oualata, supporting the restoration and digital preservation of more than 2,000 books. However, continued preservation of these documents now relies on the dedication of a handful of enthusiasts like Ben Baty, who does not live in Oualata year-round.

“The library needs a qualified expert to ensure its management and sustainability because it contains a wealth of valuable documentation for researchers in various fields: languages, Quranic sciences, history, astronomy,” he said.

Oualata’s isolation hinders the development of tourism – there is no hotel, and the nearest town is a two-hour journey across rough terrain. The town’s location in a region where many nations advise against travel, citing the threat of rebel violence, further complicates prospects.

Efforts to counter the encroaching desert have included the planting of trees around Oualata three decades ago, but Sidiya admits these measures were insufficient.

A number of initiatives have been launched to rescue Oualata and the three other ancient towns inscribed together on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1996. Each year, a festival is held in one of the four towns to raise funds for restoration and investment, and to encourage more people to remain.

As the sun sets behind the Dhaar mountains and the desert air cools, the streets of Oualata fill with the sounds of children at play, and the ancient town briefly springs back to life.

Advertisement

Advertisement