Peacemaker or peacebreaker? Why Kenya’s good neighbour reputation is marred

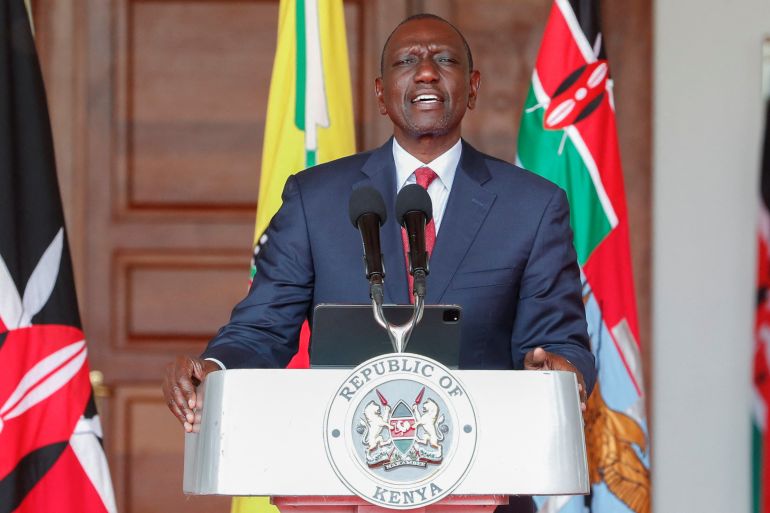

From DRC to Sudan, analysts say, President Ruto’s friendliness with regional rebel groups positions Kenya as a country that ‘takes sides’.

By Shola LawalPublished On 6 Mar 20256 Mar 2025

On a weekday in February, politicians and military men packed into a popular events centre in Nairobi’s central business district and came to a consensus over forming a new government.

But instead of the red and black Kenyan flag, a Sudanese one adorned the hall. In place of Kenyan politicians, everyone seated was allied with Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group whose ongoing war with the Sudanese armed forces (SAF) has shattered that country.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

A massive outcry – from the Sudanese government and people as well as several foreign governments, including Turkiye and Saudi Arabia – has followed the RSF’s moves. However, outrage has also been directed at the Kenyan government for its seeming support of the paramilitary. The SAF-led government, currently based in Port Sudan, recalled its ambassador to Kenya in February. When the RSF again met in Nairobi last week to sign a “transitional constitution”, the SAF did not mince words.

“These clear positions affirm the Kenyan Presidency’s irresponsible stance in embracing the genocidal RSF militia,” the SAF-led government said in a statement on Sunday, adding that Kenya was a “rogue state”.

Advertisement

The RSF’s signing of the “Sudan Founding Charter” last month in effect paves the way for a parallel government in RSF-held territories, including in parts of the capital, Khartoum, and the western region of Darfur.

For analysts, the fact that such a divisive move was allowed in Nairobi means Kenya is not neutral.

“In football parlance, this is a diplomatic own goal,” Abdullahi Boru Halakhe, a Kenyan-based policy expert who also works for Refugees International, told Al Jazeera. The consequences of such a move on Kenya’s reputation are costly and the damage “will take a while to fix”, he added.

It’s only the latest diplomatic mishap that the government of President William Ruto has waded into recently. Clashes with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) over the hosting of rebel groups in Nairobi in late 2023 are still simmering. Analysts said Ruto’s positioning in the two events is a significant policy turnaround for a country once viewed as an impartial regional leader where peace negotiations between warring factions in Somalia and at one time Sudan were once held.

A dividing line in Sudan?

Fighting in Sudan first broke out in April 2023 after Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, the leader of the RSF, and General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the SAF chief, fell out. The two leaders had earlier participated in a coup that ended a transitional government that included civilians, but a subsequent power struggle ended their alliance.

Advertisement

More than 60,000 people have been killed in the war, and 11 million have been displaced. Both sides are accused by the United Nations of possible war crimes in the fighting. However, there are more grievous allegations against the RSF, whose fighters are mainly from Darfur’s nomadic “Arab” tribes. The UN said last year that the RSF had waged a “horrific” campaign against the sedentary “non-Arab” Masalit people in West Darfur and the attacks could be “indicators of genocide”. In January, the United States declared the RSF was committing a “genocide” and it was targeting people “on an ethnic basis”.

While Egypt and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a coalition of northeast African states that includes Kenya and Sudan, have tried to negotiate peace talks, they’ve been largely unsuccessful.

After the first RSF meeting in Nairobi in February, Kenya’s government defended itself against the backlash from Sudan and opposition politicians at home. In a statement, Foreign Secretary Musalia Mudavadi said Nairobi was in fact playing a peacemaking role.

“The tabling of a roadmap and proposed leadership by the RSF and Sudanese civilian groups in Nairobi is consistent with Kenya’s role in peace negotiations, which requires it to provide non-partisan platforms for conflict parties to seek resolutions,” Mudavadi said.

But some Sudanese disagreed. Although there were civilian groups at the RSF meetings, including some from Darfur, Sudanese political analyst Shaza El Mahdi said that because the SAF was not present, any peace negotiations would be null.

“I don’t buy it at all,” El Mahdi told Al Jazeera about Mudavadi’s statement. “For the RSF, this meeting with civilians is more of a branding thing to wash their image. It signals big alarms for us as Sudanese because the RSF is putting the first stone in a line that will divide Darfur from the rest of the country. It’s a divisive move.”

Advertisement

Besides, the RSF likely only used Nairobi as a launchpad to generate some form of legitimacy, added the analyst, who works for the Center for International Private Enterprise. That move, though, has affected how Sudanese perceive the Kenyan government, she said.

“Personally, I don’t support the RSF or the SAF because both sides have been perpetrators and should face justice,” El Mahdi said. “But then many Sudanese people do prefer the SAF and see it as the better alternative, and now people believe that Kenya is supporting the RSF against Sudan.”

Some observers pointed to a “friendship” between Ruto and Hemedti as one possible reason for Nairobi’s seeming camaraderie with the RSF.

In January 2024, Ruto hosted Hemedti, who was on a regional tour and had been welcomed also in Uganda and Ethiopia to the ire of the SAF government. Then talk of a “bromance” between Ruto and Hemedti intensified after Ruto travelled to Juba, South Sudan, for a state visit in November. On the presidential jet with Ruto was Hemedti’s brother and RSF Deputy Commander Abdulrahim Dagalo, who has been sanctioned by the US for his role in the war.

Others, however, pointed to a recent economic agreement between Kenya and the United Arab Emirates, whose government is believed to back the RSF although it denies this. The deal, signed in January, will see the UAE double investments in Kenya. Already, Nairobi is waiting to receive a $1.5bn UAE loan to fund budget deficits that occurred from a borrowing spree during the previous administration.

Peacekeeping troops and ‘high-waist pants’

In December 2023 in a similar fashion to the Sudan debacle, Nairobi played host to rebel leaders from the DRC, causing a deep row between the two countries, even as the Kenyan government insisted it was trying to make peace.

Advertisement

Amid the creeping advance at the time of the M23 – a rebel group that the UN said is backed by Rwanda and that has seized key eastern DRC cities in recent weeks – its leader Bertrand Bisimwa met with Corneille Nangaa, the DRC’s former elections commission chief-turned-rebel, to announce a political alliance. Their news came from the lobby of a Nairobi hotel.

That stunned political observers not just because of Bisimwa but also because Kenyan soldiers at that time were leading peacekeeping troops from the East African Community (EAC) to enforce a shaky ceasefire between the DRC’s army and a host of armed groups, including the M23.

Several problems had already arisen between Nairobi and Kinshasa over the M23. The DRC had for months accused the Kenyan-led peacekeepers, who were first deployed in November 2022, of “cohabiting” with the rebels.

That’s because Kinshasa wanted EAC troops to face and stop the M23 – its biggest headache. But the Kenya-led force refused to go on offensives, arguing that its mandate was only to oversee the withdrawal of armed groups and enforce agreed ceasefires. Tensions grew. In parts of the DRC, protests and riots broke out as angry Congolese attacked peacekeepers from the EAC as well as the UN for failing to stop M23 violence. In December 2023, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi sent the EAC forces packing.

It was against that backdrop that the M23 head arrived in Nairobi. In angry statements after the meeting, Kinshasa ordered Ruto to arrest the two rebel leaders, but that request was bluntly refused.

Advertisement

“Kenya is a democracy,” Ruto responded in a release. “We cannot arrest anybody who has issued a statement. We do not arrest people for making statements, we arrest criminals.”

Now barely a year later, the M23 has gone on to seize the major eastern towns of Goma and Bukavu. The war has displaced hundreds of thousands of Congolese, and at least 7,000 people have been killed since the fighting intensified in January, according to the DRC government.

“How can someone who is attempting to mediate peace also be accommodating people who have taken arms against the Congolese people?” Kambale Musavuli, a Congolese human rights advocate and analyst with the US-based Center for Research on Congo-Kinshasa, told Al Jazeera.

“Regardless of what explanation Ruto may have given, I think he tried to enter the issues of the Congo. One will ask, if a belligerent Kenyan citizen who has picked up guns is allowed to organise a press conference in Kinshasa, would Kenya have responded the same way [that Ruto did]?”

Many Congolese, Musavuli continued, were already not fond of Ruto because of a “close friendship” with Rwandan President Paul Kagame and due to a perceived “condescending” attitude towards the country.

The analyst referenced a gaffe Ruto made while on the campaign trail in 2022 that had angered DRC diplomats and hurt many Congolese. Speaking to a crowd of small-business owners, Ruto had promised more agricultural revenue because he planned to open avenues to sell livestock to the DRC, saying they “have a population of 90 million but don’t own any cows”. Ruto had also called the Congolese, a people who “wear high-waist trousers”, referring to a style common in Congolese music videos. He later apologised for the gaffe after Congolese politicians expressed anger.

Advertisement

“When the elections for Ruto were being held, we in the DRC were not rooting for Ruto. We wanted an alternative because we already knew his attitude towards us,” Musavuli added.

From peacekeeper to side-taker?

Long before its present rifts with its neighbours, Kenya was once seen as a broker of peace in East Africa.

In 2004, under the leadership of President Mwai Kibaki, warring factions in war-racked Somalia gathered in Nairobi to agree to a deal that would form a federal parliament and end the bloody civil war that had raged on and off since the 1991 fall of the dictator Mohamed Siad Barre.

Just a year later, Kenya again led and played host to the Sudanese Comprehensive Peace Agreement, a peace framework that helped end the Sudanese civil conflict and eventually paved the way for the founding of the nation of South Sudan in 2011.

Now under Ruto’s administration, Kenya appears to not only be struggling to uphold that image but also to be actively causing trouble, analysts said. The seeming alliances with not one but two foreign armed factions since Ruto took office in 2022 have harmed Kenya’s former regional standing as a country with diplomatic might and weakened its reputation as an honest interlocutor, according to experts.

Even internally, Kenya has been rocked by tensions not seen since the country’s 2007 post-election crisis. Youth-led protests racked the country in June and July last year as thousands marched against Ruto’s plans for higher taxes. Weeks in, protesters were shot at by the Kenyan police. At least 50 people were killed, hundreds injured and many others remain missing, according to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. Kenyans on social media are still calling on Ruto to step down with the hashtag: #RutoMustGo.

“Sudan and the DRC both have exposed Kenya’s diplomatic Achilles heels,” Halakhe said. “For all its internally fractious politics, Kenya’s foreign policy – while not particularly principled – was not self-harming.”

Advertisement

All that has changed, he added.

“Now [Kenya] has taken sides. From being the place where peace processes are negotiated to now being engaged in genocide-washing is a steep decline of Kenya’s diplomatic prestige.”