EXPLAINER

Not just AfD: What’s the BSW, Germany’s rising populist left party?

The party founded in January espouses anti-NATO, anti-immigrant populist rhetoric while promoting left-wing economics.

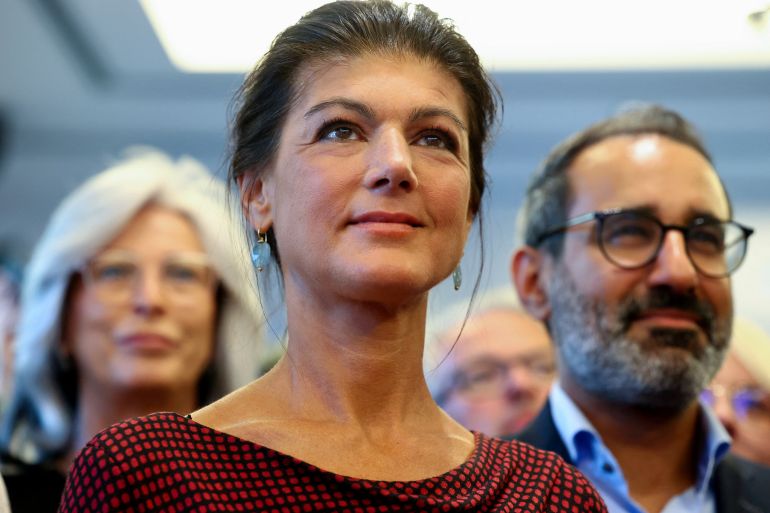

Germany’s BSW party leader Sahra Wagenknecht reacts after first exit polls in the Thuringia state elections in Erfurt, Germany, on September 1, 2024 [Christian Mang/Reuters]By Nils AdlerPublished On 25 Sep 202425 Sep 2024

It’s the new kid on the block in German politics — and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) is making waves.

A little more than nine months after its birth, the BSW, a new populist party, is rapidly emerging as a major political force in Europe’s largest economy, after stunning gains in recent state elections. The latest among them was in Brandenburg, on the outskirts of capital Berlin, where the BSW secured 13.5 percent of the vote, coming third behind the federally ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD) of Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

On paper, the BSW belongs on the left – the hard left, even. But it advocates an unusual mix of left-leaning economic policies and anti-immigration rhetoric.

Experts say its success lies in cannibalising Germany’s left while also borrowing from the nationalist policies of the AfD – all while using its unorthodox brand of populism to appeal to apathetic voters.

So what is the BSW, how is it shaking up German politics, and could it be a key player in national elections scheduled for next September?

What is the BSW?

The BSW is a new left-wing alliance founded on January 8 primarily by former members of The Left party (Die Linke), a party with roots in the former communist party that ruled East Germany.

Its eponymous leader, Sahra Wagenknecht, who was born in East Germany to an Iranian father and a German mother, had previously led The Left party, which she had been a member of since its foundation in 2007.

During her time with The Left party, she positioned herself on the far left, opposing her party when it sought to form ruling coalitions for state governments with centrist, social-democratic parties. Then, in 2023, Wagenknecht had a major showdown with The Left after she organised what was described as a Ukraine peace rally in Berlin, but which critics said promoted Russian talking points. At the rally, organisers called for a ban on weapons exports to Ukraine and for pressure on Kyiv and Moscow to negotiate an end to the war.

By late 2023, a split appeared inevitable. She left the party last October.

Is the BSW already a force to reckon with?

In many ways, yes.

When Wagenknecht, the former co-leader of The Left, quit the party, she was joined by nine members of parliament from the party, who also are now part of the BSW, giving the fledgling party a voice in the Bundestag even before it contested any national election.

And in a spate of state elections in recent weeks, it has demonstrated, say experts, that it has an appeal that is spreading – and that far outstrips the support that The Left party, from where the BSW emerged, today enjoys.

On September 1, the party won 11.8 percent of the vote in Saxony and 15.8 percent in Thuringia, coming third in both those elections. Brandenburg added to that pattern, with another third-place finish and double-digit vote count in the state’s September 22 election.

What has led to the success of the BSW?

The BSW’s “personality-driven, national-populist campaigns” have drawn much of its support from The Left party but also galvanised people who had not voted in previous elections, Rafael Loss, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations told Al Jazeera.

He said it has benefitted from being the “new kid on the block” and hence can promote a programme that is “vague on policy beyond general statements about the economy, education, and climate”.

The location of the three recent state elections in eastern Germany has also benefitted the BSW.

Matt Qvortrup, professor of political science and international relations at Coventry University, told Al Jazeera that the BSW’s success in those areas represents a “nostalgia” among some voters for the communist era in East Germany between 1949 and 1990.

He said that the BSW’s promises of strong social security rooted in left-wing policies appeal to voters who had felt more protected by the welfare state before reunification.

Loss highlighted Wagenknecht’s “omnipresence” in German media as having helped raise the profile of her new party.

He noted that she has a “unique ability to deliver pointed one-liners while avoiding specifics, for example, calling for peace in Ukraine without actually explaining how she’d get Russia, the aggressor, to the negotiating table”.

BSW and AfD: Do they overlap on some issues?

Yes, but even there, there are differences.

Consider immigration. The BSW, Qvortrup said, has embraced anti-immigration rhetoric, blaming large-scale immigration for pressures on social systems in Germany’s cities and communities. The AfD has rallied against asylum seekers, multiculturalism and Islam since its foundation in 2013.

The two parties share similar views on immigration, “painting a picture of Germany as succumbed to chaos as a result of illegal immigration”, Loss said, adding that, in fact, the number of new asylum applications has declined since it reached a peak in 2015.

Loss said that “the racist underpinnings” of the two parties’ anti-migrant stances “are more visible with the AfD than with the BSW”, even though he says the BSW “seeks to constantly connect immigration to criminal behaviour”.

The BSW’s approach to immigration plays into a sense of national pride that differs from the AfD’s view, Qvortrup said. He said the BSW’s nationalist rhetoric is rooted in nostalgia for a more homogenous system that had existed in East Germany.

This type of romanticisation differs from the nationalistic rhetoric of the AfD, which promotes an unapologetic celebration of traditional German culture and seeks to tap into frustration that displays of national pride are perceived as inappropriate or problematic because of associations with Nazi Germany, he said.

What about Ukraine and Russia?

The BSW and AfD “share a rejection of two core tenets of post-war Germany’s international orientation: its anchoring in the political West through formats like NATO, and Europe’s integration,” Loss said.

Both parties, he noted, share an affinity for authoritarian strongmen of the world, such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping.

This stance has led both parties to criticise sanctions on Russia and oppose sending military aid to Ukraine.

However, Loss said that despite a shared scepticism of NATO, they diverge in their view of Germany’s armed forces, the Bundeswehr.

“The AfD’s national conservatism views authority, hierarchy and the military with great admiration, whereas the BSW would like to see nothing more than Germany getting out of NATO and disarm,” he said.

Will Germany’s Social Democrats ally with the BSW?

It’s a growing possibility.

Scholz’s SPD narrowly beat the AfD in the latest Brandenburg elections.

The SPD has ruled out ever working with the AfD, but with its usual allies underperforming in the recent state elections, the party might be forced to consider working with the BSW.

If the BSW and the SPD would combine their seats in a new state parliament they would obtain a majority.

Deutsche Welle reported that the SPD General Secretary Kevin Kuhnert had told German public media on Monday that talks with the BSW were in sight.

However, Qvortrup said both parties will want to avoid a coalition.

The SPD will look to avoid being associated with less “palatable” populist views propagated by the BSW.

And he said there would be little incentive for the BSW to become a governing party, as it currently benefits from its image as an anti-establishment protest party.