EXPLAINER

Mpox crisis: Why do African countries struggle to make or buy vaccines?

African countries produce less than 2 percent of the vaccines the continent needs, experts say.

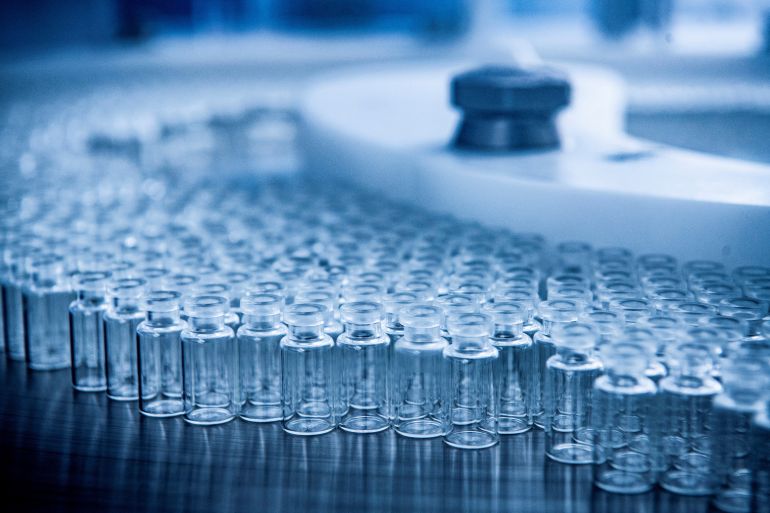

A handout picture of a Bavarian Nordic smallpox and mpox vaccine manufacturing line [Bavarian Nordic/Carsten Andersen/Handout via Reuters]By Shola LawalPublished On 12 Sep 202412 Sep 2024

After months of delay due to logistics, the first sets of mpox vaccines have finally begun arriving in Democratic Republic of the Congo, donated by Western countries.

The Central African nation is the epicentre of a new mpox outbreak that led the World Health Organization (WHO) to sound its highest alert level last month. In 2024, more than 20,000 mpox cases have been reported and more than 500 people have died. The virus is present in 13 African countries, as well as in some European and Asian nations.

However, neither DRC nor other African nations produce the vaccines that could slow the spread of mpox and eventually help it to die out. Instead, the countries at the heart of the health crisis have had to rely on promises of vaccine donations from abroad.

Japan and Denmark are the only countries with mpox vaccine manufacturers. Promised donations from Japan to DRC did not materialise in August due to administrative delays, officials said. Last Thursday, the European Union donated about 99,000 doses to DRC; then on Tuesday the United States, via USAID, delivered 50,000 doses. The vaccines came from Danish pharmaceutical Bavarian Nordic.

DRC, a country of about 100 million people, aims to roll the doses out in the hardest-hit South Kivu and Equateur regions.

The vaccine dilemma that DRC faces mirrors the situation most African countries found themselves in during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, rich countries like the US invested funds in developing and manufacturing vaccines, but also bought up most of the stocks, while African countries had to rely on subsidised shipments that many experts say took too long to arrive.

Author and doctor Amir Khan, writing on Al Jazeera during the COVID pandemic, blamed “vaccine nationalism” – a situation where rich governments sign agreements with pharmaceutical manufacturers to supply their own populations with vaccines in advance of them becoming available for other countries.

That attitude, Dr Khan added, is “incredibly shortsighted” because viruses spread across borders and therefore need a global response.

Here’s why African nations have a vaccine production problem and what some countries are doing to change that:

What is Africa’s vaccine production capacity?

African countries presently produce less than 2 percent of vaccines used on the continent, according to the WHO. By 2021, there were fewer than 10 vaccine manufacturers in Africa – based in Senegal, Egypt, Morocco, South Africa and Tunisia.

These manufacturers have modest capacities, and produce fewer than 100 million doses, explained William Ampofo, a virologist with the National Vaccine Institute of Ghana and CEO of the African Vaccine Manufacturing Initiative, in a submission to the WHO.

“This severely limits vaccine availability in disease emergency situations, as there is no immediate readiness to repurpose facilities for large-scale production through partnerships,” Ampofo noted.

A nurse prepares vaccines [File: Paul White/AP]

Which African countries are producing vaccines?

Vaccine manufacturers by country include:

South Africa

Afrigen: Produces COVID-19 vaccines. The start-up is also partnering with the WHO to lead the mRNA Technology Transfer Programme which aims to train scientists in low- and middle-income countries to produce mRNA vaccines.

Biovac: Biovac develops and manufactures vaccines, and also agrees to licensing deals with French pharmaceutical company Sanofi and US vaccine and drug-maker Pfizer.

AspenPharma: Produces COVID-19 vaccines.

Senegal

Institut Pasteur Dakar: IPD has manufactured Yellow Fever vaccines for 80 years.

Morocco

Marbio: Also called Sensyo, the company was developed in partnership with Swedish pharmaceutical Recipharm during the COVID-19 pandemic and was set to produce COVID vaccines. However, its processes are being assessed for quality and production is yet to begin.

Egypt

Holding Company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA): Produced COVID-19 vaccines (China’s Sinovac), Hepatitis B, Tetanus, and cholera vaccines.

Tunisia

Institut Pasteur Tunis: Produces COVID-19 and flu vaccines.

What are the challenges to producing vaccines in Africa?

Analysts said that vaccine production capabilities are hindered by financial and technical challenges.

If that is to change, African countries need to mobilise funds and assure investors of unwavering commitment, said Mogha Kamal-Yanni, policy lead at the advocacy organisation, People’s Medicine Alliance (PMA).

“It was quite clear during the pandemic that the inequality was enormous and that if you want supply, you have to invest in local production,” Kamal-Yanni said. “There has to be a lot of financial and procurement commitment. India has reached very high efficiency in production because when you increase scale, the costs come down. So African companies need support from the beginning to compete with the likes of India.”

South Africa’s AspenPharma, which has said it is in talks to develop mpox vaccines, has voiced concerns about market readiness.

“We need to know that we have a commitment to volumes,” CEO Stephen Saad told the Reuters news agency last week. “We can’t be told that we’re going to get a billion [orders] and then it becomes nothing,” he said.

African countries already producing vaccines have been overly focused on their internal markets at the moment, and not on exports to their neighbours, analysts noted, compounding the problem.

On the other hand are technical issues like procuring equipment, building physical facilities capable of producing millions of doses, and hiring specialised staff.

Richer countries have “technology transfer” agreements with their African counterparts. South African manufacturer, Afrigen, is being supported by the EU and other rich countries to be a “transfer hub” sharing techniques with other African manufacturers.

However, experts noted that companies were not always willing to share technologies or general knowledge with their counterparts. In 2022, German pharmaceutical BioNTech attempted to sideline the WHO-backed Afrigen, according to an investigation by medical journal, BMJ.

A consultancy company hired by BioNTech – kENUP Foundation – sent documents to the South African government claiming the WHO hub was “unlikely to be successful and will infringe on patents”, BMJ reported. Instead, kENUP pushed BioNTech’s proposals to establish a factory in the country.

Manufacturers would also need to meet rigid quality standards. Currently, many African countries do not have regulatory and quality assurance processes that comply with global standards, according to the German development agency, GIZ (PDF). There also is no consistent, continent-wide regulatory process that will assure vaccine manufacturers of access to the entire African market.

In addition, patent laws, which require explicit permission to reproduce vaccines, have hindered African manufacturers in times of emergencies.

It took two years for developing countries to get their richer counterparts and the World Trade Organization to waive patent restrictions on COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic, in one example. The agreement, championed by South Africa and India, allowed manufacturers to produce vaccines or patented ingredients or elements without the authority of the patent holder for five years.

A health worker shows a cervical cancer vaccine HPV Gardasil, during a vaccination campaign on the street in Ibadan, Nigeria [File: Sunday Alamba/AP]

How do African countries get vaccines?

African countries mostly rely on organisations of the United Nations such as the WHO and UNICEF, and GAVI, a partnership between governments and private stakeholders, to get vaccines during emergencies.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, several African countries were provided with vaccines through the COVAX initiative, a partnership between GAVI, WHO, UNICEF, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

COVAX ensured some countries that could not pay for vaccines got doses for free, funded by richer nations – although they still paid for deliveries and other operational costs. African countries, as well as Asian and Latin American nations, benefitted from the programme.

Analysts have noted, however, that the COVAX alliance faced several issues and was characterised by chaotic and opaque operations.

Several countries, including Libya, did not receive their COVAX orders on time, and had to make separate arrangements with pharmaceutical companies, meaning they paid twice. In a 2023 study, researchers concluded that COVAX failed to meet its goals and that vaccines arrived more than a year late for poor countries who were forced to pay again for less effective doses.

The main reason for that, the study noted, was simply the unavailability of shots, despite the alliance’s efforts. “COVAX was outcompeted for limited supply of vaccines by richer counties who enjoy greater purchasing power,” the researchers wrote.

Activists and experts have for long denounced the inequities in the global vaccine market that often see African and other developing nations on the backfoot. Those inequalities, already simmering, were only further enhanced by the pandemic, they said.

The effects could be dire, for all countries, warned Didier Mukeba Tshilala of medical NGO Doctors Without Borders, known by its French initials, MSF. Dr Tshilala, who manages East and West Africa operations for the charity, has been on the front lines of DRC’s mpox fight, and has witnessed firsthand what the effects of delayed vaccinations can mean. Viruses spread exponentially when vaccines are unavailable, he said, and if particularly potent, could mutate, potentially becoming more deadly.

“Certain vaccines considered of global health interest should see their price significantly reduced by pharmaceutical firms and their patents should be placed in the public domain to allow the manufacture of generics,” he said, referring to global pharmaceuticals who lead vaccine production processes.

African nations, too, have a role to play, he added. “[They] need to unite via the African Union to provide Africa CDC with the necessary financial means to allow Africa to produce vaccines on the African continent. With vision and political will, a transfer of skills is theoretically possible between rich countries and Africa.”

What are countries doing to step up production?

The AU has set goals for the continent to produce 60 percent of its vaccines by 2040, however, with the limited capabilities, it is unclear if this aim can be achieved.

Countries like Kenya are trying to kick off production, but face challenges. The East African nation signed a partnership agreement with Moderna to build a mRNA vaccine facility in the country in 2021. However, in March 2024, Moderna announced it was pausing that plan because of reduced demand, following the waning demand for COVID-19 vaccines globally.

African manufacturers might need to focus on honing their “fill/finish” capacity for now, while collaborating with established production partners and slowly building up production capacity, Professor Ampofo of Ghana’s NVI told the WHO.

This entails filling up vaccine vials with the shots and packaging and labelling operations – the tail end of vaccine production. There are some 80 African fill-finish companies at present.

Kamal-Yanni of the PMA adds that prioritising funding for local research and development efforts, as well as quality facilities, is crucial too, at least in the short term. That is also likely to signal to investors that there’s commitment, she said. “It won’t get African countries to produce vaccines tomorrow, but it could get them to produce in some years.”