But for all the ways Chicago represents Democratic ideals, critics say it has also exemplified the party’s failings and divisions.

Looming large over the upcoming Democratic National Convention is the spectre of an earlier convention in Chicago that ended in unrest and violence.

In 1968, the Democratic Party was facing questions about police violence, racial inequality and an unpopular overseas war, just as it is today. Then, as now, a turbulent election season was unfolding.

Still, the party assembled in Chicago for its 1968 Democratic National Convention.

But the Democrats were in turmoil. Less than three months prior, the assassination of Senator Robert F Kennedy, who was widely expected to be the Democratic nominee, left the party in disarray.

A late entry into the Democratic race — Hubert Humphrey — ultimately became the nominee. He did not win a single primary, a point of some contention.

Also looming over the convention was the unpopular Vietnam War, which sowed deep divisions within the party. Chicago was a tinderbox. Protesters poured into the streets to vent their frustration. Chicago police were there waiting for them.

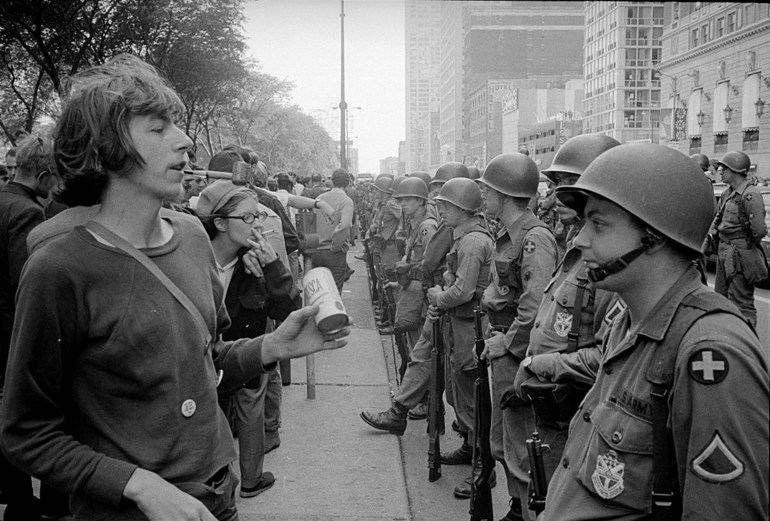

Images of their clashes have since become seared in the national consciousness.

Demonstrators face National Guard soldiers across the street from the Hilton Hotel in Grant Park, site of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, on August 26, 1968 [Warren K Leffler/Library of Congress handout via Reuters]

At the time, political consultant Don Rose, 93, was the media spokesman for the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), which called for demonstrations against the war.

“The most important thing I observed were horrendous beatings on the last day of the convention,” Rose said. “I think the world has seen famous scenes people refer to as the Battle of Michigan Avenue, where police were beating the hell out of protesters.”

Rose believes the present-day Democratic Party should look back on that time as an example of what not to do.

“The main lesson to be learned is that protesters should be given the opportunity, as the First Amendment in the United States [says], of being able to protest,” he said.

He added that it was important to allow the protesters “within earshot” of the convention “so that they get their voices heard” by the high-ranking party members inside.

Already, questions about how to respond to protesters have swirled around this year’s Democratic ticket.

Hundreds of demonstrators are expected to gather outside the 2024 convention site to protest Democratic support for Israel’s war in Gaza.

And critics have seized on Walz’s track record as governor during Minnesota’s racial justice protests in 2020 to probe whether he reacted quickly and decisively enough.

Those questions are part of larger rifts within the Democratic Party, between centrists who often prefer a sterner approach to criminal justice and progressives who seek reform and an end to police misconduct.

Still, Cowan said the current optimism surrounding the Harris-Walz campaign may overshadow any protests outside this year’s convention in Chicago.

“The protest may be strong, but the protesters may find themselves to be in a very small minority because of the tremendous enthusiasm for [Harris],” Cowan said.