World

Fax machines permeate Germany’s business culture. But parliament is ditching them

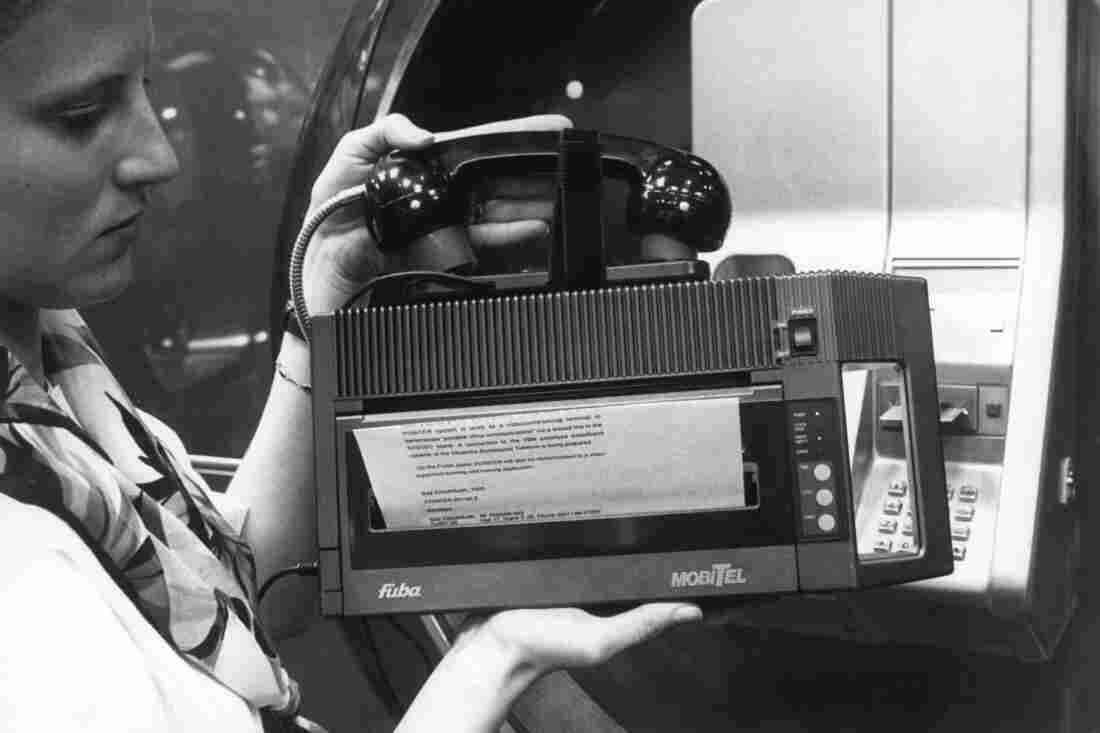

The CeBit technology fair in Hanover, Germany, March 24, 1990, shows a portable fax machine that weighs 3 kilos (6.6 pounds) and can be connected to any telephone via acoustic couplers.

Holger Hollemann/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Holger Hollemann/AFP/Getty Images

BERLIN — The sound of the 1990s still resonates in the German capital. Like techno music, the fax machine remains on trend. According to the latest figures from Germany’s digital industry association, four out of five companies in Europe’s largest economy continue to use fax machines and a third do so frequently or very frequently.

Much as Germany’s reputation for efficiency is regularly undermined by slow internet connections and a reliance on paper and rubber stamps, fax machines are at odds with a world embracing artificial intelligence.

But progress is on the horizon in the Bundestag — the lower house of parliament — where lawmakers have been instructed by the parliamentary budget committee to ditch their trusty fax machines by the end of June, and rely on email instead for official communication.

Torsten Herbst, parliamentary whip of the pro-business Free Democrats, points out one fax machine after the other as he walks through the Bundestag. He says the public sector is particularly fond of faxing and that joining parliament was like going back in time.

“When I was elected in 2017, I walked to my office and there was a fax machine inside. I thought it was a mistake,” Herbst says, wide-eyed. “I called the administrator at the Bundestag, asking why did you send me a fax machine? I don’t need it.” He says he was dismayed by the response: “Oh, yes, you need it. If you want to send an inquiry to the government, use the fax machine!”

Herbst spearheaded the initiative to get rid of fax machines from parliament. He was able to convince the budgetary committee it was a worthwhile cost-cutting initiative. But he says that unplugging the devices is only half the battle.

“When you send a message with a fax machine, you sign it and then it’s valid,” Herbst points out. “That’s the difference to email, which does not have the same status in our legal system.” As a member of Germany’s governing coalition, Herbst has been working on legislation to make email a legally binding form of communication.

Herbst says the fax machine’s long-exalted legal position in Germany boils down to widespread distrust of anything that isn’t written in pen and ink on actual paper. The result, he says, is excessive bureaucracy.

“We have a lot of procedures in Germany where you print out papers or you need a PDF file — and in the end it will be printed out, which makes no sense,” Herbst says, shaking his head.

Germany’s military has also come under recent criticism for reliance on the fax machine.

In March, the International Monetary Fund warned that if Germany wants to boost economic growth, it must reduce red tape and finally get round to digitizing properly.

Thorsten Alsleben, who runs the neoliberal think tank New Social Market Economy Initiative in Berlin, agrees. “Fifty-eight percent of companies we surveyed say they don’t want to invest in Germany because of bureaucracy,” Alsleben says. “That’s worse than taxation, worse than high energy prices, worse than anything else.”

As part of a campaign calling on the government to reduce red tape, Alsleben has opened what he calls “the most German of German museums,” the Bureaucracy Museum.

Among the objects on display is a 10-foot stack of files representing the paperwork needed to install one wind turbine. Another is a photograph of a mailbox with the label: “Please deposit online forms here.”

Alsleben says this obsession with red tape is the result of a risk-averse mindset among Germany’s public servants.

“Government officials, not the politicians, but the officers, they say, ‘No, no, no. If we reduce this bureaucracy, this and this could happen and that’s too dangerous,'” Alsleben laments. “And then everybody is scared and says, okay, no, then we cannot reduce it.”

For some, though, paperwork means business. Marcus Schulze runs an office equipment supplier that offers a comprehensive fax repair and maintenance service.

He took over from his father 30 years ago and says when it comes to fax machines, it’s business as usual. “Our customers include hospitals, doctors offices, law firms, courtrooms, you name it!” Schulze says.

He shows off his vast collection of old typewriters, desk phones, floppy disks and fax machines which now adorn the shelves of his own office. He says they’re not just decor; he often rents out older fax models to production companies shooting films set in the early 1990s.

Newer models are also in demand, but not for fictitious offices. “Last year, we received an order from the Berlin police for 60 brand-new fax machines.”

Schulze says many customers believe fax machines to be more secure than email. A pronounced preoccupation with data protection in Germany is often cited as a reason why many here still prefer to pay by cash than credit card.

He says the only other country that competes with Germany for its love of analog technology is that other large economy, Japan — whose fax manufacturers, he says, are still the best.

Back at the Bundestag, lawmaker Herbst checks the Foreign Affairs Committee machine before sending something, to see if it’s still connected. As it starts to beep and hiss, he sighs and watches as the paper scrolls through the machine.

Grinning, Herbst says the last fax he sent was to propose the motion to get rid of parliamentary fax machines.