41 minutes ago

About sharing

Saudi authorities have permitted the use of lethal force to clear land for a futuristic desert city being built by dozens of Western companies, an ex-intelligence officer has told the BBC.

Col Rabih Alenezi says he was ordered to evict villagers from a tribe in the Gulf state to make way for The Line, part of the Neom eco-project.

One of them was subsequently shot and killed for protesting against eviction.

The Saudi government and Neom management refused to comment.

Neom, Saudi Arabia’s $500bn (£399bn) eco-region, is part of its Saudi Vision 2030 strategy which aims to diversify the kingdom’s economy away from oil.

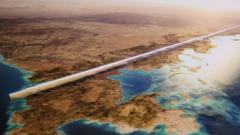

Its flagship project, The Line, has been pitched as a car-free city, just 200m (656ft) wide and 170km (106 miles) long – though only 2.4km of the project is reportedly expected to be completed by 2030.

Dozens of global companies, several of them British, are involved in Neom’s construction.

The area where Neom is being built has been described as the perfect “blank canvas” by Saudi leader Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman. But more than 6,000 people have been moved for the project according to his government – and UK-based human rights group ALQST estimates the figure to be higher.

The BBC has analysed satellite images of three of the villages demolished – al-Khuraybah, Sharma and Gayal. Homes, schools, and hospitals have been wiped off the map.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Col Alenezi, who went into exile in the UK last year, says the clearance order he was asked to enact was for al-Khuraybah, 4.5km south of The Line. The villages were mostly populated by the Huwaitat tribe, who have inhabited the Tabuk region in the country’s north-west for generations.

He said the April 2020 order stated the Huwaitat was made up of “many rebels” and “whoever continues to resist [eviction] should be killed, so it licensed the use of lethal force against whoever stayed in their home”.

He dodged the mission on invented medical grounds, he told the BBC, but it nevertheless went ahead.

Abdul Rahim al-Huwaiti refused to allow a land registry committee to value his property, and was shot dead by Saudi authorities a day later, during the clearance mission. He had previously posted multiple videos on social media protesting against the evictions.

A statement issued by Saudi state security at the time alleged al-Huwaiti had opened fire on security forces and they had been forced to retaliate. Human rights organisations and the UN have said he was killed simply for resisting eviction.

The BBC was not able to independently verify Col Alenezi’s comments about lethal force.

But a source familiar with the workings of the Saudi intelligence directorate told us the colonel’s testimony – regarding both how the clearance order was communicated and what it said – was in line with what they knew about such missions more generally. They also said the colonel’s level of seniority would have been appropriate to lead the assignment.

At least 47 other villagers were detained after resisting evictions, many of whom were prosecuted on terror-related charges, according to the UN and ALQST. Of those, 40 remain in detention, five of whom are on death row, ALQST says.

Several were arrested for simply publicly mourning al-Huwaiti’s death on social media, the group said.

Saudi authorities say those required to move for The Line have been offered compensation. But the figures paid out have been much lower than the amount promised, according to AlQst.

According to Col Alenezi, “[Neom] is the centrepiece of Mohamed Bin Salman’s ideas. That’s why he was so brutal in dealing with the Huwaitat.”

A former senior executive of Neom’s ski project told the BBC he had heard about the killing of Abdul Rahim al-Huwaiti a few weeks before leaving his native US for the role in 2020. Andy Wirth says he repeatedly asked his employers about the evictions, but was not satisfied with the answers.

“It just reeked of something terrible [that] had been exacted upon these people… You don’t step on their throats with your boot heels so you can advance,” he said.

He left the project less than a year after joining it, disenchanted with its management.

A chief executive of a British desalination company who pulled out of a $100m (£80m) project for The Line in 2022 is also extremely critical.

“It might be good for some high-tech people living in that area, but what about the rest?” said Malcolm Aw, the CEO of Solar Water PLC.

The local population should be seen as valuable assets, he added, given how well they understand the area.

“You should seek that advice to improve, to create, recreate, without removing them.”

Displaced villagers were extremely reluctant to comment, fearing that speaking to foreign media could further endanger their detained relatives.

But we spoke to those evicted elsewhere for another Saudi Vision 2030 scheme. More than a million people have been displaced for the Jeddah Central project in the western Saudi Arabian city – set to include an opera house, sporting district, and high-end retail and residential units.

Nader Hijazi [not his real name] grew up in Aziziyah – one of approximately 63 neighbourhoods affected by those demolitions. His father’s home was razed in 2021, for which he received less than a month’s warning.

Hijazi says the photos he had seen of his former neighbourhood were shocking, saying they evoked a warzone.

“They’re waging a war on people, a war on our identities.”

Saudi activists told the BBC of two individuals arrested last year in connection with the Jeddah demolitions – one for physically resisting eviction, the other for posting photos of anti-demolition graffiti on his social media.

And a relative of a detainee in Jeddah’s Dhahban Central Prison said they had heard accounts of a further 15 people being held there – reportedly for staging a farewell gathering in one of the neighbourhoods marked for demolition. The difficulty of contacting those inside Saudi prisons means we have not been able to verify this.

ALQST surveyed 35 evicted people from Jeddah neighbourhoods. Of those, none say they had received compensation, or sufficient warning, in accordance with local law, and more than half said they had been forced out of their homes under threat of arrest.

Col Alenezi is now based in the UK but still fears for his security. He says an intelligence officer told him that he would be offered $5m (£4m) if he attended a meeting at London’s Saudi embassy with the Saudi interior minister. He refused. We put this allegation to the Saudi government but they did not respond.

Attacks on critics of the Saudi government living abroad are not without precedent – the most high-profile being that on US-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi, murdered by Saudi agents inside the country’s Istanbul consulate in 2018. A damning US intelligence report concluded Mohamed Bin Salman approved the operation. The crown prince has denied any role.

But Col Alenezi has no regrets about his decision to disobey orders regarding Saudi’s futuristic city.

“Mohamed Bin Salman will let nothing stand in the way of the building of Neom…I started to become more worried about what I might be asked to do to my own people.”

Additional reporting by Erwan Rivault.

22 February 2022

23 April 2020