Elections

Some cities allow noncitizens to vote in local elections. Their turnout is quite low

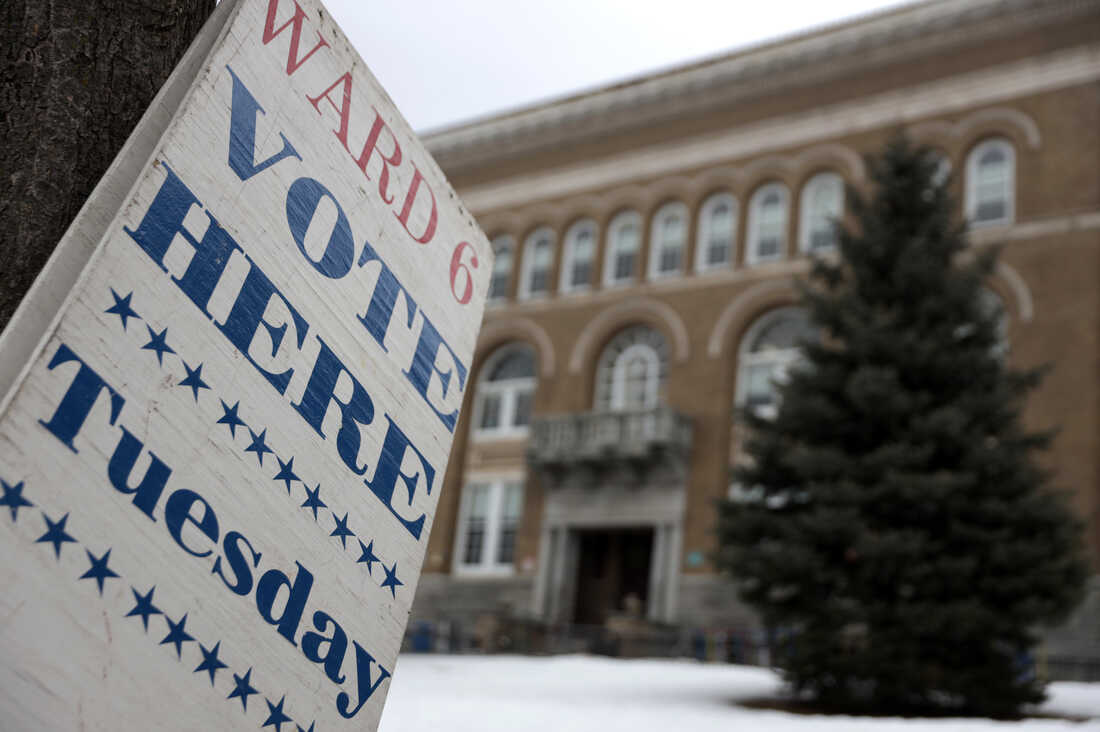

A “Vote Here Tuesday” sign is seen in Burlington, Vt., in 2020. In 2023, the city voted to allow non-U.S. citizens who are in the country legally to vote in local elections. But their turnout remains low.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Alex Wong/Getty Images

A “Vote Here Tuesday” sign is seen in Burlington, Vt., in 2020. In 2023, the city voted to allow non-U.S. citizens who are in the country legally to vote in local elections. But their turnout remains low.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

BURLINGTON, Vt. — Three cities in Vermont now allow non-U.S. citizen residents to vote in local elections.

Winooski is one of those municipalities. It just held its third local election with noncitizen voting.

“Thirteen hundred and 45 people participated in our annual city and school election,” Winooski Clerk Jenny Willingham said about March’s contests. “Eleven of those ballots cast were from our all-resident voting,” a category that includes green-card holders, refugees and asylum-seekers.

In Vermont and elsewhere, municipalities that allow noncitizen voting in local elections have seen similar low voter registration rates and turnout. Local leaders are trying to parse out why.

That’s as noncitizen voting has emerged as a national flashpoint this election year. Republicans including former President Donald Trump are pushing legislation aimed at stopping noncitizens from voting in federal elections — which is already illegal and, by all accounts, very rare.

Small numbers of ballots cast

In Winooski, getting those 11 noncitizen votes cast in March’s races took a lot of legwork for Willingham. She had the ballots printed in 12 languages and had four interpreters — speaking Burmese, Nepali, Swahili and Somali — working on Election Day.

Burlington, Vermont’s largest city, counted 62 votes by noncitizens, accounting for less than half of 1% of the nearly 15,000 total votes cast.

In Montpelier, the state’s capital, 13 noncitizens voted. There are so few noncitizen registered voters that Clerk John Odum keeps their paperwork in a half-inch blue binder.

This trend extends outside Vermont. Takoma Park, Md., legalized local noncitizen voting 30 years ago. Still, registration and turnout remain relatively low.

There are ongoing grassroots efforts in Vermont to increase voter participation among green-card holders, refugees and asylum-seekers. The League of Women Voters distributes pamphlets and holds info sessions.

The city of Burlington pays outreach workers like Jules Wetchi, an immigrant from the Democratic Republic of Congo, to connect with immigrant communities. Wetchi hosts local radio and TV shows geared at French-speaking new Americans.

The city of Burlington pays outreach workers like Jules Wetchi, an immigrant from the Democratic Republic of Congo, to connect with immigrants on noncitizen voting.

Sophie Stephens/Vermont Public

hide caption

toggle caption

Sophie Stephens/Vermont Public

“I did what they call civic education to push people to know how they should be engaged to vote, because it’s very important,” Wetchi said. “This is our second country. We are living here — we should be more engaged to the political situation.”

Fear as a barrier to voting

But Wetchi said fear is one of the barriers to the ballot box. People have told him they’re afraid they might get harassed when they vote. Others worry that voting might negatively affect their U.S. citizenship application, even if their city clerk assures them that it won’t.

Some of that fear stems from the national spotlight on this issue, which got brighter last month when Trump and House Speaker Mike Johnson pushed a measure that would add citizenship documentation requirements for voters.

Vermont Secretary of State Sarah Copeland Hanzas, a Democrat, said she understands why some Vermonters are reluctant to have their names on a list of non-U.S. citizens that’s accessible with a public records request.

“We are a nation of immigrants. So it’s wild to imagine how we got to this place where we have to worry about these things,” she said.

Winooski and Montpelier were sued by the state and national Republican parties to try to stop local noncitizen voting. The lawsuits were thrown out, but Copeland Hanzas wondered whether they added to the chilling effect.

“I’m quite certain that there are more folks who would have been eligible to vote in those local elections,” she said.

In Washington, D.C., Republicans in Congress are trying to block a law that allows noncitizens to vote in local D.C. elections. The law went into effect in January. As of April 30, there were 372 noncitizens registered in a city with around 450,000 total registered voters.

D.C. Board of Elections staff members are doing their best to keep their heads down and not let the controversy affect their work, said Executive Director Monica Holman Evans.

“I receive the quote-unquote attacks or the quote-unquote comments, commentary, opinions about it,” she said. “And I’m just very clear that I don’t take an opinion on this or any other legislation that has been passed in the District of Columbia. Our job is to enforce what’s currently in effect.”

Vermont’s local election officials also said they feel the heat from the national spotlight. They know that one slip-up, like a presidential ballot being mailed to a noncitizen, could end up on the national news.

Larger jurisdictions like D.C. have voter databases that can track noncitizen voters. Vermont doesn’t yet; the secretary of state’s office said one is in the works.

In the meantime, clerks use Excel spreadsheets and three-ring binders to track noncitizen voters. Willingham, Winooski’s clerk, keeps her noncitizen voter registrations in a manila folder in a filing cabinet next to her desk.

“I feel like I check and then I recheck just to make sure that everything is correct, that they are only voting in the elections that our charter has declared,” she said.

Despite the low turnout, the mere fact that noncitizen voting is on the books means a lot to many immigrants in Vermont. Wetchi’s mother recently made the move to Vermont from the Democratic Republic of Congo. She speaks only Swahili and a local dialect, but Wetchi said he hopes she can vote one day.

“Because her voice is very important. Her voice can change many things,” he said.

The thing is, Wetchi and his family just moved to the city of South Burlington, which doesn’t have noncitizen voting. His mom can’t vote there. But he can — he’s a full citizen. He’s even thinking about running for office one day.