In Columbia University’s protests of 1968 and 2024, what’s similar — and different

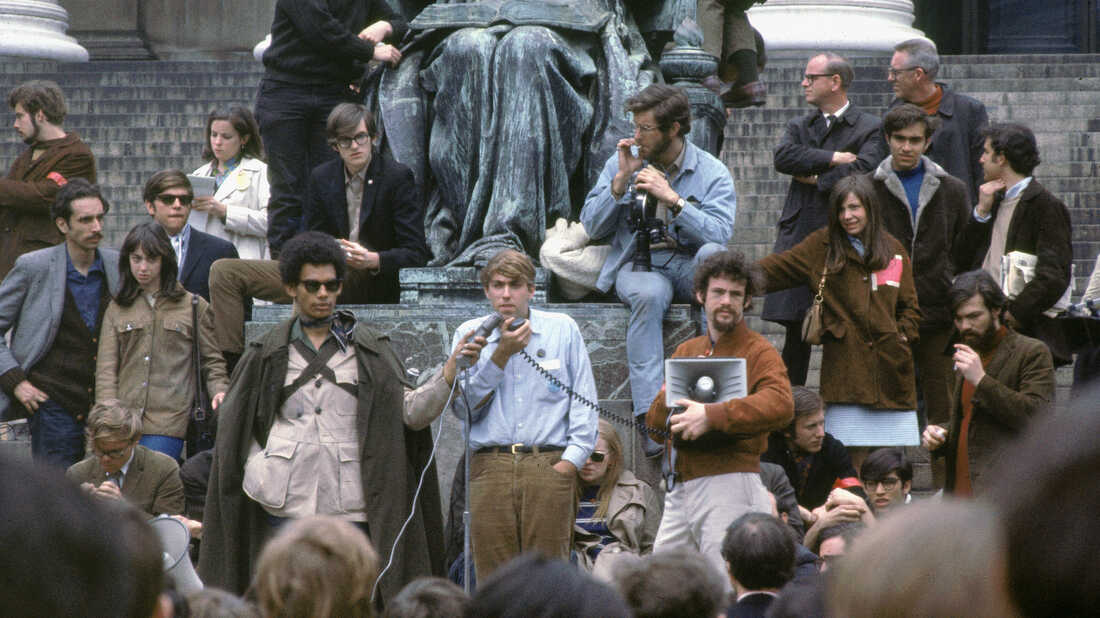

American activist Mark Rudd, center, president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), addresses students at Columbia University on May 3, 1968.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

American activist Mark Rudd, center, president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), addresses students at Columbia University on May 3, 1968.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A takeover of Columbia University’s South Lawn by pro-Palestinian students last week is drawing comparisons to 1968 — another time when police were called to clear protesting students from the campus.

There are parallels between the two high-profile events, most starkly the proliferation of similar protests around the country, as students call for an end to the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza.

But there are also differences. Here’s a quick guide:

Loading…

Several issues were at stake in 1968

For many Columbia students in 1968, their protest was motivated by anger over the Vietnam War — and changes to the military draft that were chipping away at students’ deferments, particularly in graduate schools.

The radical group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) also opposed Columbia’s links to the Institute for Defense Analyses — a think tank researching and analyzing weapons and strategies to use in Vietnam. They also wanted the CIA and military services barred from on-campus recruiting.

But others, especially the Society of Afro-American Students (SAS), were also upset that Columbia University was moving ahead with plans to take over part of a public park in Harlem, to build a gym that critics said would give only limited and second-class access to the local community.

“They were building it in Morningside Park, one of the few green spaces in Harlem,” former Columbia student and current SUNY law professor Eleanor Stein told NPR’s Michel Martin. “And we felt that it couldn’t be business as usual, that the university itself was engaging in an indefensible takeover of Harlem land and an indefensible participation and complicity with the Vietnam War effort.”

White and Black students coordinated a protest against the gym — and then hundreds of students moved from there to take over office and classroom buildings, enforcing a strike against the school.

The current president cited a “clear and present danger”

Pro-Palestinian students set up tents to hold a demonstration on campus on the same day that Columbia University President Minouche Shafik testified in Congress about reports of antisemitism on Columbia’s campus — a session that school newspaper the Columbia Spectator

Her testimony followed months of debate and argument over free speech on campus. The school’s response to antisemitism is the subject of an investigation by the House Education Committee.

One day after the campus protesters took up their position on the South Lawn, Shafik asked police to remove them.

“I have determined that the encampment and related disruptions pose a clear and present danger to the substantial functioning of the University,” Shafik said last week, asking the New York Police Department to remove protesters one day day after.

“All University students participating in the encampment have been informed they are suspended. At this time, the participants in the encampment are not authorized to be on University property and are trespassing,” Shafik said.

Pro-Palestinian protesters gather at an encampment on the Columbia University campus in New York City on April 25, 2024.

Leonardo Munoz/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Leonardo Munoz/AFP via Getty Images

Pro-Palestinian protesters gather at an encampment on the Columbia University campus in New York City on April 25, 2024.

Leonardo Munoz/AFP via Getty Images

“With great regret, we request the NYPD’s help to remove these individuals.”

When the police were called onto campus in 1968, officers were blamed for violently arresting hundreds of students, using nightsticks and horses in a chaotic scene.

In contrast police and city officials said last week that the removal of the demonstrators from Columbia’s campus was peaceful, and no injuries were reported.

But after the wave of arrests, many students returned to the campus, setting up tents once again.

The 1968 protest occupied 5 buildings and included a hostage

Reporters for Columbia’s college radio station WKCR (including longtime NPR host Robert Siegel), were present when Henry Coleman, acting dean of Columbia College, sought to confirm his status as he stood among a crowd of students in the lobby of Hamilton Hall.

“Am I to understand then, that I am not allowed to leave this building?” Coleman asked, in an archival recording.

“Let me ask,” a male student replies. He then yells, “Is he to understand that he’s not going to leave this building?”

“Yes!” the crowd roars in response.

Why did the university delay calling police in 1968?

Part of the reason seems to be race.

The morning after students occupied Hamilton Hall, Black students aligned with SAS asked white students led by the SDS to leave.

“SAS leaders later explained that the spontaneous, participatory, and less-defined politics of SDS-led white students interfered” with the Black students’ goals that centered on racial justice and equity, according to an online history exhibit assembled by the Columbia’s library system.

Conditions inside Hamilton Hall were calm and quiet compared to the “boisterous” atmosphere elsewhere, the exhibit states. But university leaders viewed the Black-held hall as a powder keg — fearing that if police were called in against the students there, Harlem’s Black community would mount a violent reaction.

“In fact, when the police entered barricaded Hamilton Hall in the early hours of April 30, the occupying students avoided struggles with the police, calmly marched out the main entrance of the building to the police vans waiting on College Walk,” according to the library’s online exhibit.

What is the legacy of the 1968 campus protest?

“Although the war in Vietnam continued for seven more years, the protesters were, in many ways, successful,” wrote historian Rosalind Rosenberg of Columbia-affiliated Barnard College. “They persuaded Columbia to put an end to classified war research, cancel construction of the Morningside Park gym, ask ROTC to leave, and stop military and CIA recruitment.”

But some divisions emerged among the students: Black protesters asked their white counterparts to leave a building due to their different approach and focus, for instance. And women who were part of both groups cited their disillusionment with being left out of positions of power, spurring their embrace of the feminist movement.